Addiction, in psychological terms, is defined as a chronic and relapsing disorder characterised by compulsive substance use and an intense desire to seek drugs, despite the negative consequences. It results in uncontrollable behaviours that can harm health, relationships, and overall quality of life. Addiction is viewed as a disease that affects the brain’s circuits responsible for reward, motivation, and self-control.

Psychological Theories Explaining Addiction

Classical Conditioning

Various psychological theories help explain addiction, one of which is classical conditioning. This theory suggests that neutral cues—such as certain people, places, or objects—become associated with drug use and later trigger cravings. For example, a recovering alcoholic might experience strong cravings just by smelling beer or seeing a familiar bar—this illustrates classical conditioning, where neutral cues (like places, smells, or objects) become associated with substance use and later trigger cravings.

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, explains how addiction is maintained through reinforcement. Drugs create powerful positive sensations, such as euphoria, which act as positive reinforcement—the individual learns to repeat the behaviour to feel good. Additionally, drug use often reduces uncomfortable states like withdrawal, anxiety, or stress. This negative reinforcement—removing an unpleasant experience—also strengthens the behaviour. In short, drug use is reinforced both by the pursuit of pleasure and the relief from discomfort, making continued use more likely.

Cognitive-Behavioural Perspective

A cognitive-behavioural perspective is a psychological approach that emphasises the interplay between thoughts, feelings and behaviours. It suggests that the interplay and the interpretation of a situation (cognition) influence our emotions and behaviour. By identifying and modifying negative or maladaptive thought patterns, this perspective aims to improve overall well-being and reduce problematic behaviours. It also emphasises that our thoughts and beliefs play a central role in shaping addiction. People may develop misleading beliefs (“I need a drink to relax”) or poor coping skills for stress.

Therapy based on this theory (CBT) helps people notice and change these thoughts and practice new skills. Large reviews confirm that CBT can meaningfully reduce substance use. Indicatively, one meta-analysis discovered that the effect of the cognitive-behavioural treatment was moderate (approximately d 0.45) in the reduction of drug and alcohol consumption. The goal is to replace fatalistic or enabling thoughts with more realistic and empowering beliefs. For example, individuals are taught to resist urges by learning healthy coping skills such as problem-solving or relaxation techniques. They are also given practical strategies for living without substances, like reinforcing the belief, “I can cope without drugs.”

The Disease Model of Addiction

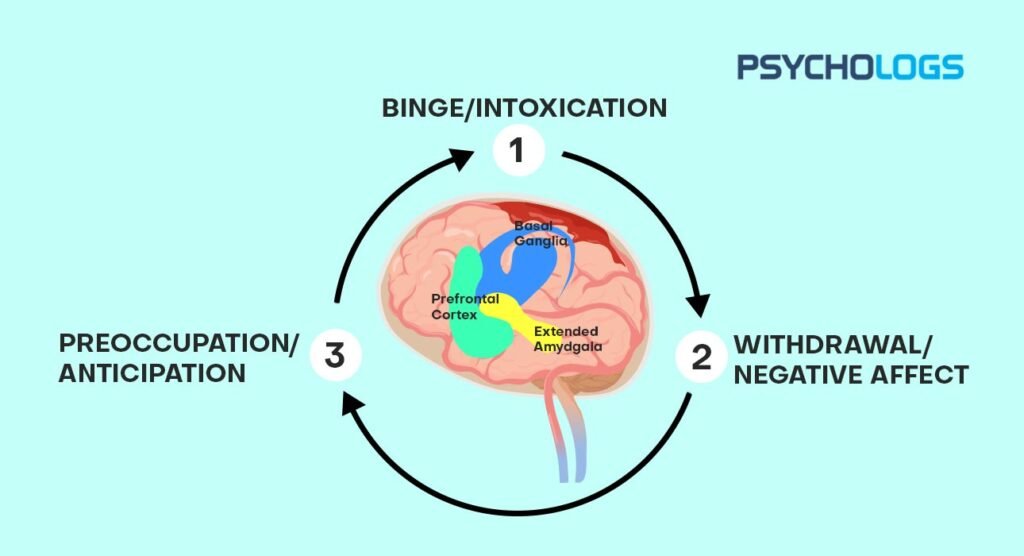

Finally, the disease model of addiction views addiction as a chronic brain disorder, not a moral failing. Neuroscience shows that repeated drug use changes brain circuits in lasting ways. In this model, addiction disrupts the brain’s reward system—making everyday pleasures feel dull—and impairs the brain’s control centres, which weakens self-regulation and willpower. For example, drugs overstimulate the basal ganglia (the brain’s “reward centre”), causing intense highs at first. Still, the circuit becomes less sensitive, making it hard to feel pleasure without the drug. At the same time, the extended amygdala (involved in stress and anxiety) becomes hypersensitive, so people feel pain or discomfort when not using and take drugs to relieve it.

These brain changes underlie compulsive use; people feel driven to use despite bad consequences. The disease model has strong evidence: NIDA researchers note that animal and human studies consistently show chronic drug use disrupts brain structures and behaviours associated with control and habit. In practice, this model leads to medical and psychological treatments to fix those brain imbalances (for instance, medications that reduce craving).

Figure: The three stages of the addiction cycle correspond to changes in key brain regions. Drugs hijack the basal ganglia (reward circuit), extended amygdala (stress/withdrawal), and prefrontal cortex (impulse control), hazeldenbettyford.org.

Understanding Relapse

What is Relapse?

Relapse, as defined by APA, refers to the recurrence of a disorder or disease after a period of improvement or apparent cure. The term also refers to the return to substance use after a period of abstinence—a relapse that, unfortunately, is common. It is best understood not as a single event, but as a process that unfolds over time.

Common Triggers

Common triggers include emotional stress and cues in the environment. Several studies concluded, those intense negative feelings, anger, anxiety, depression or boredom, are the most frequently reported relapse triggers.

Interpersonal conflict, such as arguments with loved ones, can frequently precipitate relapse. Moreover, sensory cues like the smell of alcohol, passing by a familiar bar, or even hearing a song associated with past substance use can act as powerful triggers. These cues may either evoke personal memories or create social pressure, especially when surrounded by others who are using, ultimately sparking intense cravings.

Happy occasions, such as parties, can also be triggers. A person may feel tempted to use substances even during positive events, especially if they’ve been socially conditioned to associate celebration with substance use. Concisely, an urge may come up with any recollection of previous use in internal perceptions to external stimuli like sights and sounds.

Response to Lapses

Coping skills and mindset play a critical role in preventing relapse. The Marlatt relapse prevention model highlights that what matters most is how an individual responds to a trigger, rather than the trigger itself. When a person uses effective coping strategies—such as removing themselves from high-risk situations or choosing relaxation techniques over substance use—they reinforce their self-efficacy (the belief that “I can handle this”), which in turn significantly reduces the likelihood of relapse.

On the other hand, poor coping can result in an initial lapse. What follows depends heavily on the person’s interpretation of that lapse. If it’s met with guilt, shame, or a sense of failure, it can trigger what’s known as the Abstinence Violation Effect (AVE)—a psychological spiral that often leads to a full relapse. However, if the lapse is seen as a temporary setback, rather than a complete failure, the individual is more likely to re-engage with recovery efforts and prevent further use.

That’s why relapse prevention programs don’t just teach coping skills—they also help reshape thinking patterns. Clients are taught that cravings are temporary and manageable, and that a single slip doesn’t mean failure. This cognitive shift is essential to building long-term resilience and sustaining recovery.

How does trauma influence the risk of addiction?

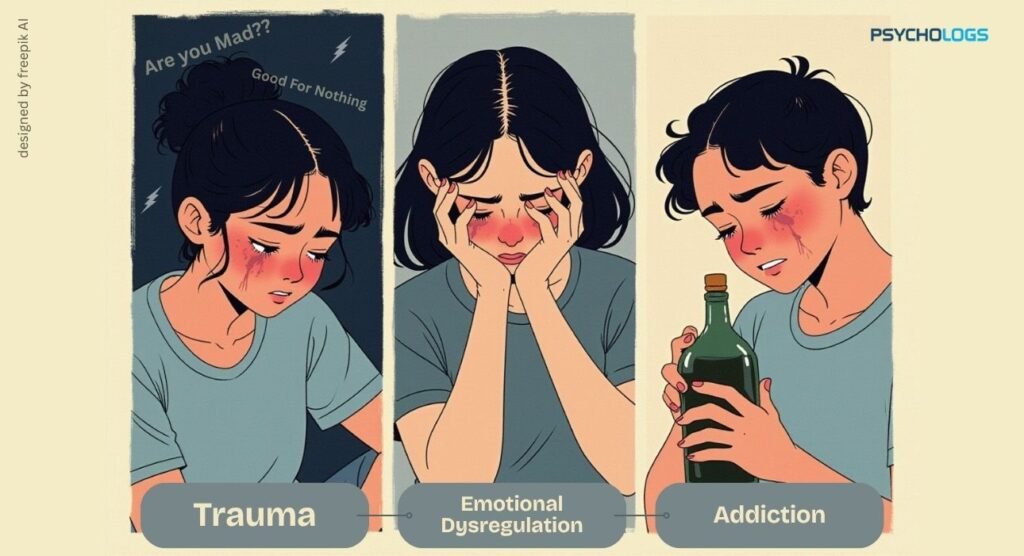

According to Psychologist and Psychotherapist Iqra A K, Addiction is rarely about the substance—it’s often about the story. Trauma rewires the brain’s alarm system, creating a state where safety feels foreign and hypervigilance becomes the norm. In this chaos, substances offer momentary relief, becoming a way to numb the pain, silence intrusive memories, or reclaim a fleeting sense of control. The brain, shaped by trauma, learns to depend on external regulation through substances because internal regulation feels impossible. When we look at addiction without acknowledging trauma, we risk treating the symptom, not the source. Trauma-informed care shifts this paradigm, offering safety, compassion, and healing where punishment and judgment have long stood in the way.

Key relapse triggers include:

- Stress and fatal emotions (anger, sadness, loneliness).

- Interpersonal conflicts in a relationship (arguments or loss).

- Peer pressure (others offering substances or using around you).

- Drug hint (places, objects, or even smells associated with past use).

- Yearning and hankering (physiological hunger for the drug).

Everyone has an individual pattern, and therefore, relapse prevention work can entail the determination of his or her high-risk situations as well as how they can be addressed.

How Trauma Influences Addiction and Relapse

How Trauma Fuels Addiction

Self-medication hypothesis

Addiction is heavily linked to traumatic situations (especially when children are involved). Traumatic experience at an early age is associated with increased risk of substance problems later, according to neuroscientific as well as survey data. Trauma usually makes individuals feel helpless and nervous; drug or alcohol use can numb such states temporarily. In the long term, the body can even be trained to associate some stimuli (such as conflict situations or trauma anniversary days) with the necessity to use the substances. In that way, the unresolved trauma may be the relapse trigger: some sudden memory or stress in a person may make them/find relief in what they have known (the substance).

PTSD and SUD comorbidity

The comorbidity of PTSD and SUD has been reported. One of the representative samples revealed that 46.4 per cent of individuals with PTSD had an alcohol or drug problem. Individuals with both PTSD and SUD are more active in symptoms and have higher relapse rates as compared to those with substance-related issues. Practically, it implies that without addressing the trauma, there is a risk that treating the addiction in isolation will not work.

Why Trauma Must Be Treated Alongside Addiction

As an example, a war veteran having PTSD may relapse in case nightmares become worse, unless his symptoms of trauma are addressed as well. Trauma-informed approach realises this: it inquires explicitly about traumas in the past, screens PTSD and promotes trauma healing as part of the recovery process. Such an example might be a case study of a man who had decades of abuse in his childhood, and he relied on alcohol to suppress the flash of frightening memories. The classic treatment enabled him to go without the addiction in the short run; in fact, he believed that something was yet lacking.

Once one of the teams started to use trauma-informed approaches (making sure he felt safe, validating his experiences, and organising caregiving among mental-health and substance-use counsellors), the client progressively started to share more about trauma and acquire more healthy coping skills. His desires not only decreased because he stopped drinking, but also since treatment of the cause (trauma) was proceeding. That is why the concepts of safety and trust are the priorities in trauma-informed care: before bigger healing could happen, safety and trust are the essentials.

Risk of relapse without trauma recovery

Trauma is both a cause and a consequence of substance use disorders. Traumatic experiences – such as abuse, neglect, violence, or serious accidents -frequently underlie the development of addiction. Research shows that approximately 46% of individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also struggle with a substance use disorder, and the reverse is also true—those with substance issues often carry unresolved trauma.

According to the SAMHSA, there is a strong correlation between trauma exposure and increased vulnerability to substance misuse. Many individuals turn to drugs or alcohol as a way to self-medicate the psychological pain associated with trauma, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, or emotional numbness. Unfortunately, this coping mechanism often leads to dependency, and when trauma symptoms are left unaddressed, they can easily trigger relapse even after a period of sobriety.

How do you help clients rebuild their sense of self after addiction?

According to Psychologist Farhana Nazneen, when it comes to trauma-informed therapy, it prioritises safety, trust, and empowerment. It is that approach which acknowledges the presence of trauma in a person’s life and its impact on their well-being. This type of therapy can be used to rebuild their sense of self after addiction. Few things can be given more importance than establishing a supportive environment, showing compassion and acknowledging the person’s struggle. Giving importance to fostering self-awareness, helping people to recognise their positive qualities and assisting them to discover their meaningful goals and core values. People with previous addiction can also be given therapies like CBT, EDMR, DBT or other similar therapies to address the underlying trauma and teach them certain coping strategies to manage their anger, cravings and triggers. More importance should be given to relapse prevention by developing a personalised plan and help clients maintain sobriety and help in prevention of relapse.

Trauma-Informed Care: Concepts and Principles

What Is Trauma-Informed Care?

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is a clinical and organisational approach that recognises the widespread impact of trauma and aims to avoid re-traumatisation. As conceptualised by SAMHSA, trauma-informed care involves two core commitments:

- Understanding the prevalence and impact of trauma across all client populations and staff levels.

- Embedding trauma awareness into policies, procedures, and daily practices, ensuring that every aspect of treatment is informed by an understanding of trauma.

Crucially, trauma-informed care does not require every clinician to be a trauma specialist. Instead, it requires that every interaction, intervention, and environment be designed with trauma sensitivity in mind.

Trauma-Informed Strategies and Their Impact

| Strategy | Impact on Recovery |

|---|---|

| Screening and Integrated Treatment (ask about trauma; treat trauma and SUD together) | The clients would feel respected and would not be on guard. Physical and emotional safety will make the clients less anxious and focus on the healing process, which helps to improve adherence to therapy. |

| Creating Safety and Trust (stable routines, trained staff, clear rules) | Hearing others’ stories reduces isolation and stigma. Peer support fosters hope and provides practical strategies that have worked for similar people. |

| Enfranchisement (shared decision making, goal setting) | Giving clients control and options (e.g. choice of therapy activities) builds confidence. When people feel heard and capable, motivation for change and adherence to treatment grow. |

| Peer Support and Community (support groups, mentors with lived experience) | Gives practical skills in ways to cope with triggers of trauma and cravings (e.g. relaxation or grounding skills). Better coping means fewer breakdowns when exposed to stress. |

| Coping Skills Training. The research fields include (stress management, emotion regulation, mindfulness) | Tailoring care (e.g. women-only groups if needed, multilingual counsellors) removes barriers. Clients are more likely to stay in treatment when they feel understood. |

| Sensitivity (respect for gender, culture, identity) | Ensures the program truly practices trauma-informed care consistently. Well-supported staff provide more empathetic care; lower staff turnover means more stable relationships for clients. |

| Staff Training and Self-Care (staff learn TIC principles and how to avoid burnout) | Tailoring care (e.g. women-only groups if needed, multilingual counselors) removes barriers. Clients are more likely to stay in treatment when they feel understood. |

Evidence for Trauma-Informed Care

Research continues to support the effectiveness of trauma-informed care in substance use treatment. For instance, a February 2024 study conducted in a residential program for young adults found that implementing a structured trauma-informed model led to significant reductions in substance use and notable improvements in mental health. Three months after treatment, participants showed a marked decline in drug and alcohol consumption (effect size d = 0.67), alongside reduced symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Both clients and staff rated the trauma-informed program as highly satisfactory and beneficial.

A 2024 systematic review of trauma-informed interventions in substance use settings reported consistently positive outcomes. Across multiple studies, the implementation of trauma-focused policies and treatments was linked to reduced substance use, fewer trauma-related and mental health symptoms, and higher treatment retention rates. Programs that trained staff in trauma-informed care, conducted routine trauma screening, and provided integrated counselling saw greater success—more individuals completed treatment and maintained sobriety.

Additional evidence comes from trials involving individuals with co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use disorder (SUD), where integrated treatment approaches have shown promising results. These interventions typically combine trauma-focused strategies—such as exposure therapy or coping skills training—with addiction counselling. Findings consistently suggest that addressing trauma symptoms alongside substance use leads to better outcomes than treating addiction alone. For example, one study reported that veterans receiving integrated PTSD and SUD treatment experienced greater reductions in depression and relapse risk compared to those who received standard relapse-prevention therapy.

In conclusion, the trauma-informed approach helps break the cycle of self-medication by addressing the root trauma and its lasting effects. It enhances—rather than replaces—traditional addiction treatment by removing one of the most persistent barriers to recovery. Both government and clinical research support its value, particularly for individuals with complex, trauma-laden histories, where conventional models alone often fall short.

Conclusion

Addiction is not simply the compulsive use of substances—it is often a reflection of emotional pain, complex psychological processes, and, in many cases, deep-rooted trauma. It alters the brain and reshapes behaviour patterns in ways that are not easily reversed through willpower alone. Psychological models such as classical and operant conditioning, cognitive-behavioural theory, and the disease model of addiction offer valuable insights into both the origins of addiction and the mechanisms that sustain it. Relapse prevention is a critical component of long-term recovery. It requires addressing both internal triggers—such as stress, emotional pain, and unresolved trauma—and external cues, like people, places, or situations associated with substance use. Conventional treatments that focus solely on abstinence often fall short when they fail to consider the traumatic roots of addiction.

Trauma-informed care offers a transformative alternative. It creates a therapeutic environment grounded in safety, trust, empowerment, and emotional sensitivity, helping individuals not only overcome addiction but also heal the emotional wounds that often accompany it. A growing body of evidence shows that trauma-informed approaches reduce relapse rates, improve mental health outcomes, and enhance treatment retention. To truly support lasting recovery, mental health professionals, policymakers, and communities must integrate trauma-informed principles into addiction treatment. Recovery is not merely about stopping substance use—it is about rebuilding a life with dignity, purpose, and stability. By addressing trauma at its roots, we don’t just treat addiction; we restore the human being behind it.

FAQs

1. Which addiction is hardest to quit?

Nicotine addiction is often considered the hardest to quit due to its intense physical dependence, frequent use patterns, and strong behavioural cues. Other substances like heroin, alcohol, and methamphetamine are also extremely difficult to quit due to severe withdrawal symptoms and psychological dependence.

2. Can addiction be cured?

Addiction cannot be cured in the traditional sense, but it can be effectively managed and treated. Like other chronic conditions (e.g. diabetes or hypertension), long-term recovery is possible with the right combination of therapy, support, lifestyle changes, and sometimes medication.

3. Are addiction and obsession the same thing?

No, addiction and obsession are not the same, though they can be related.

- Addiction is a compulsive dependence on a substance or behaviour despite harmful consequences, often involving physical and psychological changes.

- Obsession is a persistent, intrusive thought or urge that causes distress but doesn’t necessarily involve compulsive behaviour or substance use.

Addiction often includes obsession, but not all obsessions lead to addiction.

References +

References +

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2020). The Science of Drug Use and Addiction: The Basics. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/media-guide/science-drug-use-addiction-basics

- Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. (2016). Facing Addiction in America. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals report.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- Back, S.E., Waldrop, A.E., & Brady, K.T. (2009). Treatment challenges associated with comorbid substance use and posttraumatic stress disorder: Clinicians’ perspectives. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2709782

- Courtois, C.A., & Ford, J.D. (2009). Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders: An Evidence-Based Guide. https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/4317078

- Galanter, M., Kleber, H.D., & Brady, K.T. (Eds.). (2015). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. 5th Edition. https://www.appi.org/Products/Addiction/Substance-Abuse-Treatment

- Najavits, L.M. (2002). Seeking Safety: A Treatment Manual for PTSD and Substance Abuse. https://www.seekingsafety.org

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2022). Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction (Research Report). https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction

- Briggs, E.C., Greeson, J.K.P., Layne, C.M., Fairbank, J.A., Knoverek, A.M., & Pynoos, R.S. (2012). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/

- Kearney, L.K., Wechsler, H., & Rounsaville, B. (2024). Integrating trauma informed care into substance use treatment: Results from a randomized feasibility trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2024.108965

- SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. Screening for Trauma: Essential First Step in a Trauma-Informed Approach. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). (2020). Trauma-Informed Care: A Primer for Substance Abuse Providers. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/trauma-informed-care-primer-substance-abuse-providers

Leave feedback about this