Picture yourself hurrying through your day when your foot is abruptly caught by a chair leg. You mumble, “Why would you do that?” without thinking. It’s more frequent than we may think to talk to inanimate objects, whether it’s to reprimand furniture, console a cherished stuffed animal, or express gratitude to a car for a good ride. Why do we do it, though?

The Roots of Emotional Connection

Psychiatrists describe this tendency as anthropomorphizing, which is the process of giving non-human things human characteristics, feelings, or intentions. According to Dr. Melissa Shepard, it is a logical progression of human empathy and creativity. This conduct is frequently the result of emotion or nostalgia. Deep emotions can be evoked by objects associated with important life experiences. For example, an old pair of jeans may hold memories of a fun moment in life, while a childhood teddy bear may represent consolation during trying times. Kim Egel, a therapist, emphasizes how strong attachments frequently make it emotionally difficult to part with such things.

Another factor is projection. Individuals may project their emotions onto things, giving them the characteristics of loneliness, joy, or annoyance. When a plant is neglected, for example, we may see it as “sad,” indicating our awareness of its state. This projection frequently acts as a stand-in for interpersonal communication, satisfying an unfulfilled need for connection.

Read More: Object Relations Theory: How Early Relations Determine the Course of Our Life

The Influence of Culture and Media

Cultural narratives are essential at the same time. Viewers have been conditioned to sympathize with objects by films such as Beauty and the Beast and Toy Story. By giving inanimate objects a human face, these tales make them approachable and emotionally compelling. Lilianna Wilde, the inventor of TikTok, talks about how she felt bad about replacing her annoying shopping cart, and her audience members who had similar situations also expressed this concern.

These behaviours are reinforced by cultural norms and activities outside of movies. In Japan, for example, the idea of “Tsukumogami” encourages respect and care for common objects by depicting them as possessing spirits. These cultural viewpoints emphasize the universality of anthropomorphism by promoting emotional attachment to objects.

When Attachment Becomes Concerning

Although anthropomorphizing is usually trivial, severe instances may indicate deeper problems. Daily living can be disrupted by Delusional Companion Syndrome, an uncommon illness in which people believe objects have emotions. In a similar vein, neurodivergent people may feel more emotionally attached to objects. If these attachments cause problems with routines or decision-making, such as hoarding habits or trouble throwing things away, Dr. Shepard suggests getting professional assistance.

Read more: The Hidden Limitations of AI

The Empathy We Extend to Technology

This inclination extends beyond tangible items to technology, such as AI and robotics. After NASA’s Opportunity rover sent out its farewell message, “My battery is low, and it’s getting dark,” people all across the world lamented its “death.” Widespread empathy was evoked by the rover’s human-like message, demonstrating our capacity to develop emotional connections with machines.

This behaviour is further illustrated by interactions with AI, such as chatbots and virtual assistants. According to Dr Marlynn Wei, while human-like bots might arouse empathy, too-lifelike robots can cause discomfort by causing the uncanny valley effect. Wei questions if artificial intimacy alleviates loneliness or poses new problems, posing ethical questions regarding AI friendship.

Read More: The Role of Chatbots in Mental Health Services: How Does It Impact People?

Objects as Emotional Anchors

Objects frequently act as emotional anchors, assisting people in processing emotions or overcoming difficult situations. For example, a journal may serve as a secure outlet for feelings, and a travel memento may bring back happy memories of discovery and delight. These items frequently serve as stand-ins for significant events, persons, or locations. This attachment is particularly evident during grief. Holding onto a loved one’s belongings can provide comfort and a sense of connection, even after their passing. Experts suggest that these attachments can aid the grieving process, offering a tangible way to remember and honour those who are no longer with us.

Read More: The Acceptance Stage of Grief

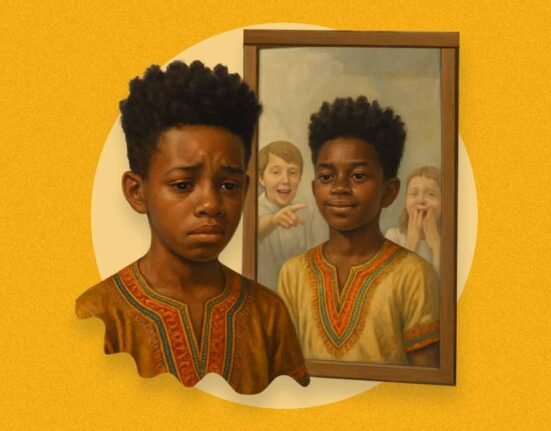

The Role of Imagination and Play in Children

Children naturally extend their imaginations by anthropomorphizing objects. They can explore emotions, exercise social skills, and develop their imagination via pretend play, such as throwing tea parties with stuffed animals or making up adventures for toy cars. This kind of play is essential for cognitive and emotional development, according to psychologists. A sense of peace and safety often comes from children’s attachment to items, such as a favourite blanket or toy. These “transitional objects” provide relief during stressful or transitional times, assisting individuals in navigating the unknowns of growing up.

Balancing Attachment with Practicality

Achieving a balance is crucial, even though emotional attachments to things might enrich our lives. We can healthily manage these attachments if we know why they occur. Understanding that these emotions frequently represent deeper emotional needs can promote self-reflection and personal development. Decluttering techniques like Marie Kondo’s “spark joy” philosophy, for example, encourage people to have thoughtful relationships with their possessions and help them get rid of things that are no longer useful.

Read More: How Childhood Experiences Affect Mental Health

Anthropomorphism in the Digital Age

Our natural ability to anthropomorphize has increased with the development of technology. By simulating human connection, virtual assistants such as Siri and Alexa encourage consumers to treat them as friends. According to research, despite these technologies’ unconsciousness, users frequently employ kind words when interacting with them, praising them or expressing regret for errors. By encouraging players to develop emotional bonds with virtual characters or avatars, the gaming business also benefits from anthropomorphism. Despite being intangible, these digital relationships have the power to arouse deep emotions, making it difficult to distinguish between simulation and reality.

Read More: How to Manage Technostress and Enhance Digital Wellness

A Reflection of Our Humanity

Although it may appear insignificant, anthropomorphizing items serve as a powerful reminder of our common humanity. It challenges us to examine ourselves, consider our relationships, and, in the end, accept the feelings that define who we are. We can learn more about the complex ways we interact with the environment around us by comprehending this behaviour. It makes sense that we look to items for consolation and company in the modern era, where interpersonal relationships can occasionally feel fragile. Even in unexpected ways, these objects— whether they be a loud shopping cart, a childhood souvenir, or a reliable device – remind us of the need for human connection.

Read More: How Psychologists Turn Therapy Resistance into Progress

Conclusion: Bridging The Gap Between Sentiment and Practicality

Anthropomorphizing demonstrates our empathy and creativity and is more than simply a strange habit. Although the majority of cases are normal and even helpful, being aware of the underlying feelings can help us carefully control our attachments. Examining the effects of these behaviours is crucial as technology advances and our interactions with AI expand. In the end, conversing with inanimate objects is a reflection of our need to relate to others, make sense of the world, and discover significance in the ordinary. It’s a habit that cuts across all countries, ages, and periods, serving as a reminder that humanity can be found even in the absence of life.

FAQs

1. Why do I scold or blame things like chairs or doors when I accidentally bump into them?

This reaction helps release frustration or stress in the moment. It’s a natural way of coping with minor accidents and feeling some sense of control over the situation.

2. Why do I find it hard to throw away old or broken household items?

You may associate these items with memories or significant life events. Letting go can feel like losing a part of your personal or family history, making it emotionally challenging.

3. Why do I talk to appliances like my washing machine or microwave?

Talking to appliances adds a sense of companionship and acknowledgement to mundane tasks. It’s a way of expressing gratitude or bonding with things that make daily life easier.

4. Why do I struggle to declutter my home, even when I know I need more space?

Decluttering often triggers emotions tied to nostalgia, guilt, or attachment to memories. It’s hard to part with items that feel like symbols of important moments or connections.

5. Why does my child talk to toys or pretend household objects have feelings?

Children use imagination to process emotions, practice social skills, and find comfort. Assigning feelings to objects helps them navigate new situations or changes in the household.

References +

1. Why do some people give human feelings to inanimate objects? What experts say https://edition.cnn.com/2024/09/07/health/empathize-inanimate-objects-anthropomorphize wellness/index.html#:~:text=%E2%80%9CIt’s%20common%20for%20humans%20to,when%20said% 20object%20is%20isolated.

2. The development of thoughts about animate and inanimate objects: implications for research on social https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247836978_The_development_of_thoughts_about_ani mate_and_inanimate_objects_implications_for_research_on_social

3. Genuine Empathy with inanimate objects https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348455261_Genuine_empathy_with_inanimate_objects

Leave feedback about this