Ever find yourself answering emails during a Zoom call, texting a buddy, and scrolling Instagram between? You’re not alone. Multitasking is the way we feel efficient, like we’re conquering the world one notification at a time. But if you ever finish a day of intense multitasking feeling drained and somehow. Unproductive, there’s a reason for this. Let’s move a bit closer to reality about what is happening in our brains when we try to do multiple things simultaneously.

Read more: How Multitasking Affects Your Brain: Psychology of Multitasking

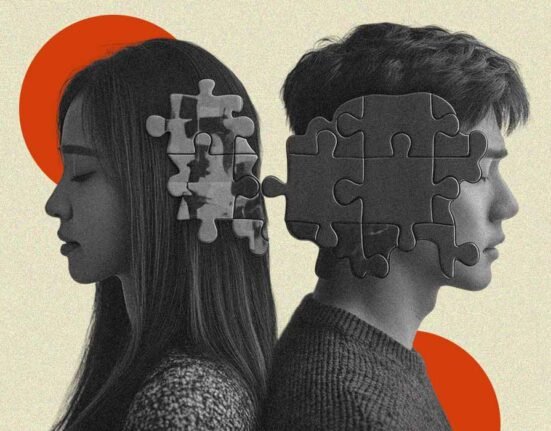

Does Your Brain Really Multitask?

Here’s the catch. While we think we’re excellent jugglers, neuroscience says otherwise. The brain is not wired to multitask with attention-intensive tasks. What it is doing is constantly switching between tasks back and forth. This is called task-switching, and it has a sneaky cost of cognitive overload. Over the past few years, multitasking has come under greater scrutiny. More and more studies have shown just how dangerous it can be, particularly when done using cell phones or other electronic gadgets while driving. That particular type of multitasking has been so deadly that numerous states have since outlawed it.

Even in the corporate world, there has been a growing awareness about the pitfalls of multitasking. Time management has long been a problem in the corporate world, and yet more voices are sounding alarms that a culture of multitasking can be reducing productivity.

In 2005, the BBC published a report on a study commissioned by Hewlett-Packard and conducted at the University of London’s Institute of Psychiatry. The results were alarming: workers who were constantly interrupted by phone calls and emails saw a reduction in IQ that was greater than twice the decrease experienced by marijuana users. The lead psychologist characterised this effect, termed “infomania,” as a grave threat to productivity.

To this, Harvard Business Review’s most famous idea of 2007 was Linda Stone’s introduction of “continuous partial attention.” This is a contemporary take on multitasking, where individuals, with continuous access to mobile phones and the internet, are perpetually on their toes. They’re always keeping watch for something new, remaining plugged into acquaintances and occurrences, out of a fear of not noticing something significant.

Imagine reading a book with someone constantly hitting your shoulder every few minutes, questioning you. You get out of place, re-read a couple of sentences, and need to recalibrate your brain to the pace of the narrative. Now imagine that all day long, with emails, texts, and pings from Slack. That’s what multitasking does to your focus: it continues to pull you out of deep thinking, causing your mind to have to reboot over and over. No wonder it drains you.

Read More: The “Rule of 3” in Productivity: How a Simple Trick Can Prevent Overwhelm

The Attention Residue Trap

Psychologist Sophie Leroy has termed this effect: attention residue. When you are transitioning from Task A to Task B, your mind isn’t releasing A right away. Part of your attention is still there. So even though you’re actually in the act of doing B, you’re not giving it your undivided attention. Imagine talking to a person when you’re still in mental replay mode for the last conversation. You’re there, but not really there. Attention residue lowers the quality of your thinking, problem-solving, and even memory.

What are the effects of Multitasking on behaviour?

Multitasking Makes You Slower, Believe it or not, but multitasking does not work. Studies have shown that it causes you to slow down by as much as 40%. It also increases mistakes. You are also more likely to forget things, miss the details, and repeat work you thought was already done.

Psychologists call this the “switch cost,” and it’s not just mental—it’s emotional, too. All that switching fatigues your brain. And a tired brain is a distracted, less creative, and grouchy one. We can gain useful information about how people distribute their attention from studies of self-regulation and attention. But much of what is written now does not get across well the special cognitive demands that interruptions create.

For instance, while studies in working with multiple goals explored how people decide to allocate their time between competing tasks, they do not look at what happens in the transitions between the tasks. Research on multitasking has shown that task switching with high switching rates entails a mental reset to cope with the distinctive requirements of each task.

While this bears some relevance to our discussion, that work is primarily interested in fast task switching and focuses on rule-based task execution. This differs from cognitive disruption when a task is interrupted and resumed subsequent to a subsequent point. There also exists complementary work on goal activation and goal shielding, which suggests that attention focusing on a goal will suppress alternative goals, but once more, it does not particularly speak to how interruptions get in the way of this process.

Read More: Benefits of Having Multitasking Skill

Your Memory Suffers as well

Let’s say you’re studying for an exam while checking texts or watching Netflix in the background. Sounds like harmless background noise, right? Not really. Studies have shown that multitasking while learning leads to poorer memory consolidation. That means your brain doesn’t store the information as effectively, and it’s harder to retrieve it later. When the brain is working on distractions, it won’t get to process the material on a deep level. That’s why you can “read” a paragraph three times and not be able to remember what was said.

Read More: Understanding Short-Term and Long-Term Memory: How We Retain What Matters

It’s usually Emotionally Draining and Mentally Exhausting

Did you ever catch yourself how performing a lot of multitasking during the day can leave you feeling weirdly tense or on edge, even though nothing much happened? That’s because you’re putting your mind through a kind of mental stress it’s not built to withstand regularly. Over and over, this produces burnout and mental fatigue. Your head isn’t just tired it’s frayed. That hazy, overwhelmed feeling is your mind’s plea: I need a break from continuously changing gears all day. It also disrupts mood regulation. The more your mind is divided, the harder it is to stay calm or grounded. Multitaskers regularly have higher rates of stress, restlessness, and even depression.

Read More: Algorithmic Addiction: Why You Can’t Stop Scrolling

You Miss Out on Life’s Details

Here’s a mind-blowing one: Multitasking can anaesthetise your awareness of the present moment. Ever eaten a meal while scrolling and then looked up afterwards, wondering how it tasted? That’s because you weren’t there. When you divide your attention, you divide your experience. Multitasking takes away little pleasures, like the aroma of coffee, or the passing sensation on the face of a friend when you’re conversing with them. In relationships, it is especially damaging. Continual partial attention makes people feel heard and not seen. That damages connection and intimacy over time.

Not All Multitasking Is Bad, Though

Now, to do good credit, not all forms of multitasking are the devil. Some things are second nature and can be paired. Folding clothes while listening to a podcast is fine because it’s only one thing that needs to be processed in the brain. Walking and talking? As smooth as cake. But when both processes require thinking and deciding, then all hell breaks loose. It’s also worth noting that certain individuals, especially those with some ADHD traits, can feel more at ease while jumping between tasks, yet long-term cognitive performance can still be affected.

How to Stop Multitasking Without Losing Your Mind

If you’ve made it this far while scanning three other tabs, relax. We’re all conditioned to multitask. But you can recondition your brain to work differently. Start small. Try:

- Single-tasking for 25 minutes (the Pomodoro technique).

- Turning off non-emergency notifications.

- Creating “focus zones” in the day where you perform a single activity.

- Mindfulness: One minute of breath awareness can reboot your mind.

Initially, when you monotask, it will be dull or even hard. That’s alright. It’s merely your brain adapting to thinking more slowly and deeply.

In the End, Less Is Truly More, Multitasking creates the illusion of efficiency and speed. But in reality, it drains our energy, scatters our attention, and makes us less satisfying. The silver lining? Your brain is superbly flexible. The more you practice single-minded attention, the better you become at it. So the next time you feel tempted to multitask three things at once, pause and ask yourself: What if I focused on just this one thing—wholly, fully, and deliberately?

FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is it so difficult to get back on track after an interruption?

Interruptions don’t just ruin our flow, they disturb how our brain processes goals and attention. Contrary to rapid task-switching, in which our mind remains engaged to some degree, interruptions cause us to disengage mentally from a task and then re-engage, an effort that is high-maintenance. Our brain needs to reorganise itself to resume where we were, and that mental “reset” consumes energy and attention.

FAQ 2: Don’t we already know how people manage multiple tasks from research on goal-setting and multitasking?

To some degree, yes. Multitasking and multiple-goal research examine how individuals divide time and attention between tasks. But these studies tend to examine how we select between goals or how we coordinate tasks in rapid succession. They often fail to account well for what happens during longer, unanticipated interruptions, such as when a meeting interrupts your work or a message sidetracks you.

FAQ 3: What is “goal shielding,” and how does it pertain to interruptions?

Goal shielding is how your brain protects your current task by inhibiting distractions or alternative goals. When you’re concentrating, your brain deliberately blocks anything irrelevant. But interruptions lower that shield, allowing other tasks or stimuli to creep back in. Getting back to the original task isn’t so much about willpower, it’s about reactivating that goal and redirecting focus, which isn’t always simple.

References +

Rosen, C. (2008). The myth of multitasking. The New Atlantis, (20), 105-110.

Crenshaw, D. (2021). The myth of multitasking: How” doing it all” gets nothing done. Mango Media Inc..

Leroy, S. (2009). Why is it so hard to do my work? The challenge of attention residue when switching between work tasks. Organisational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 168-181.

Kirschner, P. A., & De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher education, 67, 135-142.

Leave feedback about this