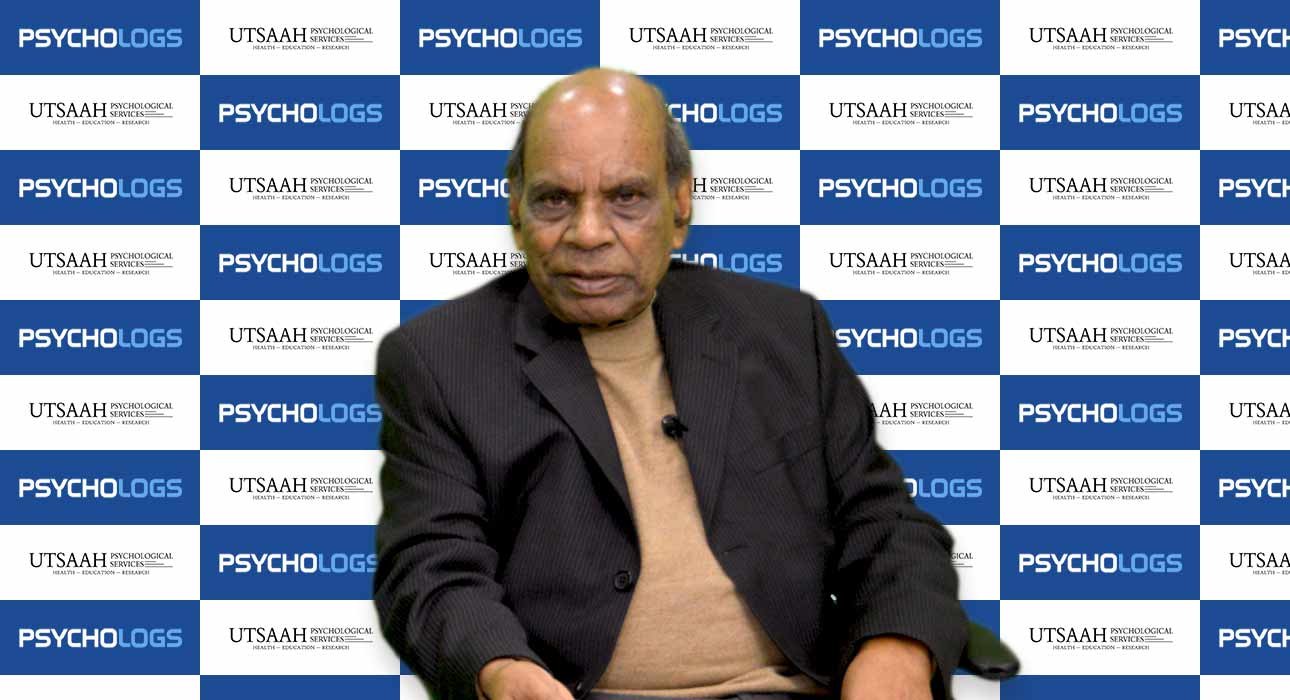

Exclusive Interview with Prof. Jagannath Prasad Das (JP Das): The person Behind the PASS Model of Intelligence

- by Arvind Otta, Jagannath Prasad Das

- January 25, 2020

- 0 Comments

- 9 minutes read

- 824 Views

This Interview was taken by Arvind Otta and originally published in Psychologs Print Version: Vol. 01 | Issue 9 September 2019

(Psychologs magazine) ISSN: 2583-4193

Q1. Defining Intelligence is challenging due to the components associated with rapid advances in understanding. How do you define Intelligence?

J. P. Das: I should say that intelligence is the total of all of the cognitive processes. It entails planning, coding of information, attention and arousal as well. Of these, the coding processes required for planning have a relatively higher status in intelligence. Planning is a broad term that includes the generation of plans and strategies, the selection from available plans, and the execution of plans. Within the connotation of planning, I would include decision-making. In my view, knowing many things is not the essence of intelligence. Instead, I believe that the ability to discriminate thinking, or discriminating intelligence, is what makes a person intelligent. This discriminating intelligence is the same as’ve Buddhi in our Indian philosophy.

Q2. As you mention in Indian Philosophy, Ekagrata “एकाग्रता” is one of the key concepts for learning. How did you keep yourself motivated and ekagra “एकाग्र” to work in this field for so long?

J. P. Das: Growing up in India, I was deeply immersed in a culture where scholarship, intelligence, and wisdom were revered qualities intrinsic to human beings. However, what intrigued me was the acknowledgement that formal education did not necessarily equate to intelligence. I witnessed many individuals in traditional communities who lacked formal schooling yet were esteemed for their wisdom and intellect.

My own grandfather exemplified this. Despite his lack of formal education, he was highly respected in the village for his wise counsel and was often sought after to assist in resolving complex matters. This experience instilled in me the belief that true intelligence lies in the ability to make decisions that benefit the community.

My academic journey further fueled my interest in intelligence. At university, I had the privilege of studying under Dr Mohsin, a professor from Scotland who held a PhD in intelligence and collaborated with Godfrey Thompson, a pioneer in the concept of multiple intelligences. Dr Mohsin’s guidance introduced me to the fascinating field of experimental psychology and intelligence testing, marking the beginning of my enduring fascination with the study of intelligence.

Q3. There is one who inspires us through the journey. God give you a long and healthy life! You have been working in the field of psychology for a long time. Who has inspired you throughout your journey, specifically during student life?

J. P. Das: I am fortunate to have been mentored by Dr Mohsin during my time in India, followed by Professor Hans Eysenck, who served as my PhD supervisor at the Institute of Psychiatry, University of London. Throughout my doctoral studies, I had the opportunity to engage with Professor Arthur Jensen, who was a postdoctoral fellow under Eysenck’s guidance. Our discussions often revolved around intelligence and the criteria for selecting students for admission to various professional schools in America, primarily based on IQ.

Jensen staunchly defended the concept of IQ, which left me intrigued by the notion that intelligence was an innate attribute and could not be significantly enhanced through improved education or enriched social environments—a perspective I approached with scepticism. Additionally, my awareness of the challenges faced by culturally disadvantaged children in India, many of whom dropped out of school by grade five, further fueled my curiosity.

As my career progressed, I found inspiration in the works of A.R. Luria and Vygotsky, whose research significantly influenced my own. Their insights, coupled with the guidance of Dr Mohsin and Professor Eysenck, have left a lasting imprint on my approach to research and writing in the field of psychology.

Q4. As you have explored many areas of Psychology, how is your work on intelligence helping researchers in another discipline?

J. P. Das: I’ll tell you what, the goal of all my research was to understand and measure intelligence. Two disabilities have fascinated me. One is intellectual retardation, and the other is a learning disability. When I started to investigate the effects of poverty and malnutrition on intellectual function, and when I attempted to understand the differences among children with intellectual retardation, my interest in intelligence (arising out of neuropsychology and cognitive psychology) did influence my work. The variety of difficulties that the so-called learning-disabled children experience cannot be measured in terms of IQ. Thus, I had to use alternative models of intelligence; that’s how my thinking evolved.

Q5. Tell us more about your PASS theory of Intelligence.

J. P. Das: This has a foundation in two branches, neurology and psychology. I thought we could operationalise how the brain works through a limited number of tests. PASS stands for planning, attention, simultaneous and successive processing. There are four major cognitive processes of the brain. Two ways we gather information are patterns and sequencing.

According to the PASS theory, information first arrives at the senses from external and internal sources, at which point the four cognitive processes activate to analyse its meaning within the context of the individual’s knowledge base. One unusual property of the PASS theory of cognitive processes is that it has proven useful for both intellectual assessment (e.g. the CAS) and educational intervention.

It is different from existing standardised tests of IQ mainly because it’s not a collection of questions that relate to school learning. Rather, it has a firm base on major functions of the brain and assumes that an individual with intellectual disability can have a variety of strengths and weaknesses in the PASS process despite their lower level of functioning.

Q6. In one of your articles, you said that if you want to develop concepts in children, you need to send them to a school that teaches in their mother tongue. We would love to hear your views on ‘How Schooling and Education in the Mother Tongue can Aid in the Learning of a Child’. Any peculiar comment in the Indian context, where parents are very firm about sending children to English medium schools, irrespective of their mother tongue.

J. P. Das: We need to understand how language develops. A pre-lingual child at the very beginning can discriminate all phonemes in any language. Gradually, the discrimination destroys and gets concentrated in the language he grows up in. So, a loss of perception of difference in phonemes happens. If you don’t grow up in a unilingual environment, you don’t acquire a grasp of any language. That is the beginning of the loss of mastery over language.

We are all aware of how it is affecting the present generation of kids. They cannot take advantage of cultural resources in their language. Comprehension is not all that the word means; unless you are extremely familiar with a language and the culture, you can’t go beyond simple meanings. So, you can’t have very much original thinking. Up to age 7, most countries teach in their mother language. In India, we don’t give a grounding in their local languages, so several local Indian languages are dying. The reason is, thinking that English has an advantage in education and jobs. We don’t transfer knowledge; this is our biggest mistake. It is a very big dilemma in our country.

Q7. We would like to know more about ‘The JP Das development disabilities centre’ at the University of Alberta, and your ongoing association with it.

J. P. Das: It was by chance that I heard about the University of Alberta, where I have been working for many years. One day, I was sitting in my office at Utkal University in Bhubaneswar, when I received a letter from the University of Alberta asking me if I would be interested in a job at the Centre for the Study of Mental Retardation. I asked my mentor, Nicholas Hobbs, president of APA. On his suggestion, I wrote to them that I’ll be glad to join as a Researcher. This started my tenure at the Centre of Study of Mental Retardation as a research professor, later as director. The centre was named after me, because of my successor and the people of this University.

This changed my life. At that time normalisation movement started in Britain, i.e. living in a community to learn normative behaviour. I became very interested in helping mentally retarded people in my own country. There are many disadvantaged children. I researched malnutrition in children in Orissa & Sri Lanka. Poverty has become a big topic in education. Chronic poverty produces chronic stress, and stress depresses learning. Once poverty is improved, stress and many other things are reduced.

Q8. Please enlighten us with some of your recent research and academic activities, including ‘Modules of Mathematics’, which is getting popular in India.

J. P. Das: Helping disadvantaged children has really encouraged me to make programmes for improvement, not only of knowledge but also of foundational cognitive skills, which help us learn how to read and how to do maths. About modules of mathematics, Researches tell us two things: to see patterns (both in language and visual), and working memory. A little bit of language and to plan and strategise. One of the strategies is working memory.

The math module emphasises the second, i.e. working memory. Comprehension vs. learning to read encourages another set of cognitive processes. Reading surely depends on sequencing. At the same time, we have to grasp the total meaning of the sentence. My programmes in reading are based on PREP and COGENT, which are commercially available. Programmes on MATH are based on planning, strategies and working memory. That’s how we approach intervention. First, we know what Science and research tell us, and then we make programmes to help.

The new test I am developing is called the ‘Brain-Based Intelligence Test’. The name comes from the idea that all intelligence comes from the brain. We are including ages 5 to 20. One thing we are measuring is Executive functions and Planning, which have cognitive flexibility, inhibition and working memory as components. We have tests for all of these. Then, we have simultaneous and successive tests, which I have modified.

It is in verbal and nonverbal forms. The uniqueness of BBIT is that it will be bilingual. To start with, in English and Hindi. We’ve already collected data on 1400 people from ages 5 to 20, each one tested individually, from 5 different parts of India. For the 15-20 age group, besides logical problem solving, we have emotionally coloured decision-making, unlike a lot of tests previously available.

As people now realise that a majority of the world’s children lag in schooling & healthcare, and have disrupted childhood. Should we be doing Intelligence testing on one academically oriented IQ scale, or should the true score include the human value of compassion and sharing & equitable distribution of resources? That would be a problem for future generations.

Q9. What are your suggestions to organisations working in the field of Learning Disability in India?

J. P. Das: Imbue in culture. Anyone not know the culture cannot advise what to do in India. Stay sensitive to culture. Then you have to see that the knowledge we create is backed by practice. We must acquire knowledge before we make improvements. Transfer of knowledge to practice is lacking.

Q10. What is your message to learners and students, and young professionals in Psychology?

J. P. Das: Knowledge! It is available easily on the Internet for free. Take good courses available. Read, don’t rote learn. The practice or profession is based on or guided by knowledge. It needs to be updated continuously. Do you have little groups of people working in the field. Acquired knowledge needs to be continuously discussed in terms of reading, experiences and possible solutions.

Reference +

Psychologs Magazine. (2019, September). Vol. 01, Issue 9. ISSN 2583-4193.

Leave feedback about this