One essential cognitive system that allows humans to store and process information for brief periods is working memory. It is fundamental to several mental functions, including comprehension, learning, and reasoning. The notion of working memory is examined in this article, along with its elements, significance in cognitive functions, and methods for improving its performance. Both classic and recent studies in the area are cited.

Definition and Components

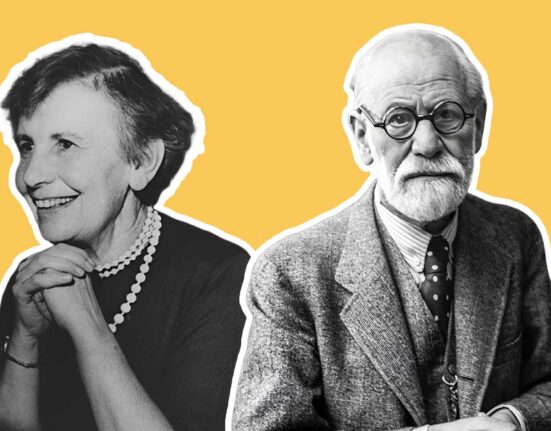

The system in charge of momentarily storing and processing data required for intricate cognitive functions including language comprehension, learning, and reasoning is known as working memory. The multi-component model of working memory, first presented by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974, has had a significant impact on cognitive psychology. The central executive, phonological loop, and visuospatial sketchpad were the three primary parts of their concept at first; the episodic buffer was added in 2000.

Read More: 6 Science-Backed Memory, Tips and Techniques

- The Central Executive serves as a supervisory mechanism, directing attention and integrating data from the episodic buffer, phonological loop, and visuospatial sketchpad. It is essential for jobs involving decision-making and problem-solving.

- The Phonological Loop stores and rehearses speech-based information, playing a key role in language comprehension and learning.

- The visuospatial Sketchpad handles visual and spatial information, important for navigation and understanding spatial relationships.

- The Episodic Buffer integrates information from the phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, and long-term memory into coherent episodes.

This model has been extensively tested and refined over the years. Baddeley’s framework provides a comprehensive understanding of how working memory operates within the brain (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Baddeley, 2000).

Importance of Working Memory in Cognitive Processes

A key component of many cognitive functions is working memory. It enables people to momentarily store knowledge, making it usable for cognitive functions including language comprehension, problem-solving, and decision-making. Studies reveal a strong correlation between academic success working memory capacity and general intelligence (Conway, Cowan, & Bunting, 2001). It is also essential for attentional management because it keeps one’s attention on pertinent tasks and helps one avoid distractions.

Assessing Working Memory

Working memory capacity can be measured using a variety of techniques, such as the digit span task and the operation span task. These exercises evaluate how many objects a person can manage and hold in their working memory at once. Individual variances in working memory capacity are correlated with variations in cognitive abilities, according to research employing these evaluations (Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999).

Read More: Sleep breathing affects memory processing: Research

Enhancing Working Memory

Because working memory is essential for several cognitive processes, scientists have looked for ways to improve it. Working memory capacity and associated cognitive functions may be improved with cognitive training activities like working memory training programs (Klingberg, 2010). These programs frequently include adaptive activities, meaning that when a person’s performance improves, the challenges get harder. This strategy is justified by the desire to exert additional pressure on one’s working memory capacity. While some research indicates that training improves working memory, there is disagreement about whether these gains extend to other cognitive processes or daily tasks (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013).

Furthermore, the possibility of alternative therapies to improve working memory has also been investigated. For example, enhanced neurogenesis and increased blood flow to the brain resulting from physical activity have been associated with improved cognitive function, particularly working memory (Smith et al., 2010). Another topic of interest is nutrition; according to some research, meals high in omega-3 fatty acids may help with working memory and other aspects of cognitive performance (Bauer et al., 2014). Furthermore, mindfulness and meditation techniques have been linked to improved working memory capacity, most likely as a result of their focus on attentional control and awareness of the present moment (Zeidan et al., 2010).

Read More: The Psychology of Memory mastery: How to remember everything you learn

Because working memory is so complex, improving it is not easy, and no one technique has been shown to work for everyone. Because it is a complex construct influenced by a range of factors, including genetics and lifestyle, therapies may need to be tailored to the individual. It is envisaged that further study will lead to the discovery of more efficient and broadly applicable working memory enhancement techniques, enabling people to experience improved cognitive function in a variety of contexts.

The Role of Technology and Software

Growing in popularity is the advancement of technologies and software programs intended to improve and train cognitive abilities, such as working memory. With continued use, these tools should be able to offer focused exercises that eventually improve cognitive function. The scientific community is still looking at the long-term advantages and transfer effects of cognitive training on routine cognitive tasks, even if some research reports beneficial outcomes from such interventions (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013).

A basic cognitive mechanism, working memory is essential to many mental functions, including learning, reasoning, and language understanding. The multi-component model that Baddeley and Hitch put forth has greatly improved our comprehension of the composition and operation of working memory. Although each person’s capacity is unique, there are techniques and tools available to improve the effectiveness of working memory. Prospective opportunities for understanding human cognition and creating therapies to improve cognitive health and performance are provided by the ongoing research into working memory and cognitive training.

References +

- Baddeley, A., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G.A. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 8, pp. 47-89). Academic Press.

- Baddeley, A. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(11), 417-423.

- Conway, A.R.A., Cowan, N., & Bunting, M.F. (2001). The cocktail party phenomenon revisited: The importance of working memory capacity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8(2), 331-335.

- Engle, R.W., Tuholski, S.W., Laughlin, J.E., & Conway, A.R.A. (1999). Working memory, short-term memory, and general fluid intelligence: A latent-variable approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 128(3), 309-331.

- Klingberg, T. (2010). Training and plasticity of working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(7), 317-324.

- Melby-Lervåg, M., & Hulme, C. (2013). Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 49(2), 270-291.

Leave feedback about this