Failing is not simply an occurrence; it is a slow, residual experience that hangs out on the edge of our minds. The initial failure is painful, the second failure hurts, and on the third failure, it begins to alter how we perceive ourselves or how we identify ourselves. Failing once is frustrating, failing twice is bothersome, but failing three times it feels like an attack! Failing gives us a tough challenge, not only because we failed and are waiting to see if we will succeed again, but because we all ask ourselves, “Is it because I am unlucky, unfit or unworthy?” But resting in between self-doubt and self-discovery is a soft reveal for us – that failing is not the end of who we are, it is just the beginning of who might become, if we decide to see it differently.

Read More: Are we prepared enough to cope with failures?

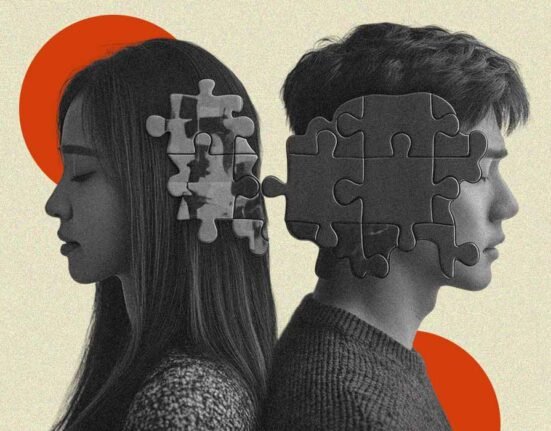

The Identity Erosion Trap

Excessive failure can lead to a psychological process, clinically referred to as identity erosion, whereby accumulated failures slowly affect a person’s identity and self-concept (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). At first, failure is simply an event: “I failed.” But if failure recurs multiple times, a person can identify with it and say, “I am a failure.” When this happens, it means that a person is undergoing “identity erosion.”

An erosion of self-worth, confidence, and behaviours is tied to the failure of self-assessment (Bandura, 1997). Erosion of self-worth and confidence is assisted by learned helplessness. When someone encounters repeated failure and, more importantly, internalises it, their actions become neutral and meaningless (Seligman, 1975). Following that, the person becomes unmotivated and disengaged. The erosion of self through self-criticism and excessive rumination is detrimental (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Unmet expectations, along with learned helplessness, can result in an ‘identity crisis’ that is marked as Erikson proposed by the loss of a coherent self, action paralysis, and role confusion (Erikson, 1968).

Erosion is a gradual process, like a campfire that is covered again and again with dirt. Each failure is like a layer of dirt that is placed, and the confidence is permanently extinguished. Over time, the person is hollow and unrecognisable. Comparisons of oneself to social norms and public failures that lead to shame reinforce isolation with one’s (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Of significance is the interpretation of failure. If the person interprets failure as data to be used toward self-growth, it helps foster resiliency (Dweck, 2006). If failure is seen as a declaration or verdict of self-worth, we unintentionally accelerate the processes that erode our identity.

Read More: Why we fear Failure and How to Overcome it, According to Psychology

The Psychology of Resilience: Why It Feels So Hard?

When we continue to try and we continue to fail, the brain is put in a precarious position where motivation conflicts with threat. With repeated failure, the stress systems become engaged, followed by stress sensitisation, which means every failure reinforces the emotional and physiological responses to stress, increasing anxiety and exhaustion (McEwen, 2007). Ultimately, this will make persistence feel increasingly impossible, as the brain begins to contextualise effort as painful or pointless.

Resilience operates through cognitive flexibility, the ability to shift our attention between emotions, thoughts, and goals (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). Studies of the neurocognitive nature of resilience show that resilient people activate frontal brain network mechanisms more effectively, enabling them to better regulate emotion and pain perception (Davidson & McEwen, 2012). They can reappraise a setback as a challenge, not a threat to their well-being, which is facilitated by the process of cognitive appraisal (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). This protects against the onset of learned helplessness.

Resilience is not about avoiding distress, but rather, being able to respond to distress adaptively. When a person can respond to stressors and emerge from the experience having changed, it indicates that they are retaining some level of neuronal plasticity; the brain’s ability to rework itself structurally, a process called adaptive learning – or the brain’s ability to shift and mold flexibly to stressors or unwanted situations and not just behave mechanically and mindlessly (Feder, Nestler, & Charney, 2009). Other factors that assist with this process are self-efficacy, social capacity, and a growth mindset (Bandura, 1997; Dweck, 2006). It is also important to remember that resilience is not a set or fixed quality, and can be developed with habitual practices that develop emotion regulation and cognitive reframing (Gross, 2015).

Read More: Emotion Regulation Across the Lifespan: Mechanisms and Outcomes

Reframing the Evidence

In the process of shifting from self-blame to self-awareness, the first stage is to identify where you engage in self-critical speech. Self-critical thoughts or behaviours arise suddenly and take root after a risk is taken, and one experiences failure. Instead of wondering “What’s wrong with me?” one can wonder “What is this kind of experience going to teach me?” It is fascinating that in this shift, failure is no longer part of the person’s identity. Expanding the definition of failure is a useful exercise. Failure is data. You can feel your emotions, such as shame or guilt, without blending with your emotions; you are not your thoughts (Neff, 2003).

Next, you can identify the specific circumstances that trigger self-blame by journaling your thoughts. Are you personalising the outcome of an event too much? Are you denying any accomplishments to appropriate luck? This shows that self-blame has begun to internalise in some form. When you try to question the belief, “I’m not good enough,” you want to ask its adherents Why is believing that wrong? What’s the proof? Where did you learn that? Many times, those beliefs get traced back to some experiences or some people in one’s life (Beck, 1976).

You can recognise and redevelop self-worth based on your self-respect: self-compassion and making small, intentional choices daily for yourself. You want to emphasise something intrinsic to yourself; show substrates (creativity, kindness, persistence) instead of a numeric pragmatism of comportment. One perspective frames this as if you are simply a plant that needs nurturing again (Neff, 2003).

Read More: Feeling Shame Is Not Good for Your Mental Health?

Conclusion

Identifying losses as failures is primarily indicative of what those failures lead us to believe about ourselves. Every failure contributes to the narrative of how we identify, or how we show up in the world, and fundamentally how we feel about ourselves. The buried truth and wreckage of received failures is that one’s identity is fluid and not in a fixed state. One can learn helplessness, reframe the narrative to something more constructive, and restore the parts of the self that one feels have chipped away. Failure is not the antithesis of resilience. Rising with awareness and the resistance of self-blame is how strength is more about how, and growing confidence is possibly about the capacity for growth. Rising, with awareness, and the resistance of self-blame is how.

FAQs

1. What is identity erosion?

Identity erosion refers to the gradual loss of self-concept and confidence due to repeated failures or setbacks, leading individuals to internalise failure as a personal identity rather than a temporary outcome.

2. Can resilience be learned?

Yes. Research shows resilience is not a fixed trait but a skill that can be cultivated through cognitive reframing, emotional regulation, and consistent self-compassion practices.

3. What is the difference between failure and learned helplessness?

Failure is an event, while learned helplessness is a psychological state in which a person believes their actions have no impact due to repeated unsuccessful attempts.

4. How does self-compassion help after failure?

Self-compassion reduces harsh self-criticism, lowers stress, and improves motivation by allowing one to treat oneself with understanding and perspective rather than judgment.

5. Why do repeated failures feel worse over time?

Repeated failures activate the brain’s stress systems, making it more sensitive to negative outcomes. This “stress sensitisation” increases anxiety and makes persistence feel emotionally heavier.

References +

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin.

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 689–695.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton.

Feder, A., Nestler, E. J., & Charney, D. S. (2009). Psychobiology and molecular genetics of resilience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 446–457.

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904.

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualisation of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. W.H. Freeman.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press.

Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320–333.

Leave feedback about this