That Jaipur afternoon is etched in Priya’s bones like a lost tune. Nine years old, bare feet warm on sun-soaked tiles, Arjun—only six and already luminous—spoke the Sanskrit shloka she’d carefully sketched for months. Their grandmother’s wrinkled face brightened up with delight as she described him as “blessed with the gift of sacred memory.” For months, their grandma had carefully attempted to teach Priya the same lyrics, her small fingers tracing the archaic writing and her mouth fumbling over foreign words. But now Arjun, three years younger, stood revelling in the golden blaze of applause.

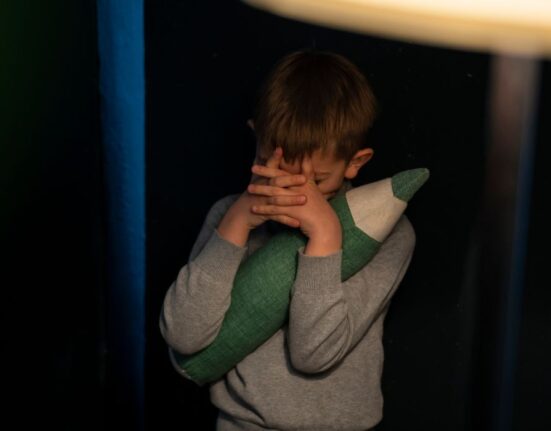

That evening, while relatives gathered around Arjun to celebrate his “divine gift,” Priya slipped away to the terrace. She sat quietly under the vast desert sky, feeling invisible for the first time in her life. Something fundamental had shifted in her world, something she couldn’t yet name but would carry with her for decades. What Priya experienced that night wasn’t simple jealousy or childish competition. Through a psychological lens, her reaction reveals something profound about human development, attachment, and the formation of identity. Which feels familiar to all of us.

Sibling rivalry, it turns out, is one of our most complex psychological phenomena—a window into how we learn to navigate love, security, and our place in the world.

The Attachment System Under Threat

When psychologist John Bowlby developed attachment theory in the 1960s, he identified something crucial about human psychology: children don’t just want their parents’ love—they need it for psychological survival (Bowlby, 1969). Our attachment system, developed over millions of years of evolution, operates like an internal alarm system, constantly monitoring the security of our most important relationships.

For a young child, the arrival of a sibling triggers this alarm system in profound ways. The older child’s brain doesn’t distinguish between a genuine threat to survival and a threat to their special relationship with their parents. The same neurological pathways that once helped our ancestors survive physical dangers now activate when a toddler sees their baby brother getting extra attention.

Dr. Bowlby’s research revealed that this isn’t an overreaction—it’s biology. Priya’s attachment system perceived her grandmother’s admiration for Arjun as a possible danger to her haven. The anxiety she felt, the sense of being displaced, arose from one of our most fundamental psychological needs: the need to feel securely connected to our caregivers.

This psychological perspective explains why sibling rivalry often intensifies during times of family stress. When parents are divorcing, moving, or dealing with financial pressures, children’s attachment systems become hypervigilant. Any sign that a sibling might be receiving more security, attention, or reassurance becomes magnified through this psychological lens of survival.

The Social Comparison Laboratory

Leon Festinger’s social comparison theory provides another crucial lens for understanding sibling dynamics (Festinger, 1954). According to Festinger, humans have an innate drive to evaluate themselves, and when objective measures aren’t available, we turn to social comparison, measuring ourselves against others who are similar to us. For children, siblings represent the most natural comparison group imaginable. Same family, same opportunities, same parents—yet different outcomes. This creates what psychologists call a “natural laboratory” for social comparison, where children constantly evaluate their worth, abilities, and place in the family hierarchy.

Constant comparison has a significant psychological influence. When your sibling excels at something you struggle with, it’s not just about that specific skill – it’s about what that difference might mean about your fundamental worth as a person. Dr. Laurie Kramer, a leading researcher in sibling relationships, explains: “Children are constantly asking themselves, ‘How do I measure up?’ And unfortunately, the most convenient measuring stick is often the sibling standing right next to them” (Kramer, 2014).

This comparison process becomes particularly intense because siblings share so many variables. If a classmate gets better grades, a child can rationalise: “Well, they have different parents, different teachers, different opportunities.” But when a sibling succeeds where they fail, that rationalisation becomes much harder to maintain. The psychological conclusion often becomes: “If my brother can do it and I can’t, something must be wrong with me.”

The Birth Order Blueprint

Alfred Adler’s birth order theory deepens our psychological knowledge of sibling rivalry (Adler, 1927). Adler recognised that our family situation produces various psychological experiences that impact our overall personality development. Adler coined the term “dethronement” to describe the psychological agony of losing their exclusive contact with their parents. From a psychological standpoint, this event frequently causes what researchers refer to as “displacement anxiety.” The firstborn must mentally adjust to sharing resources, attention, and love that were previously theirs alone.

Middle children face a different psychological challenge entirely. They never experience the exclusive attention that firstborns remember, nor do they enjoy the protected status of the youngest. Psychologically, this can create what researchers term “middle child syndrome”—a sense of being overlooked or forgotten that can persist into adulthood (Salmon, 2003). The youngest child faces their unique psychological landscape. They never experience dethronement, but they also never experience the power and responsibility that comes with being older. This can create psychological patterns of dependency or, conversely, a drive to prove their competence despite being “the baby.”

Modern psychological research has found that these birth order effects are real but not deterministic. Family size, spacing between children, gender, and individual temperament all influence how birth order affects psychological development. But understanding these patterns helps explain why siblings from the same family can develop such different personalities and coping strategies.

Read More: Birth Order Theory: How Birth Order Affects Your Personality

The Identity Formation Process

Perhaps the most fascinating psychological aspect of sibling rivalry is how it shapes identity formation. Psychologists have identified a process called “de-identification,” where siblings unconsciously develop contrasting identities to reduce direct competition (Schachter et al., 1976). If one sibling becomes “the academic one,” another might gravitate toward athletics or creative pursuits. This isn’t random—it’s a psychological strategy for carving out a unique niche within the family system. Each child seeks to become irreplaceable in their way, to find an area where they can excel without direct comparison to their siblings.

This de-identification process serves important psychological functions. It reduces direct competition and helps each child develop a sense of individual identity. However, it can also limit authentic self-expression if a child avoids certain interests solely because a sibling has already claimed that territory. Dr. Terri Apter, who has extensively studied sibling relationships, notes: “The process of becoming different from our siblings is one of our earliest experiences in identity formation. We learn who we are partly by figuring out who we are not” (Apter, 2007).

The Lasting Psychological Impact

The psychological patterns established through sibling relationships don’t remain in childhood—they become part of our psychological blueprint for understanding relationships, competition, and our place in social hierarchies. Adults who experienced intense sibling rivalry often carry forward certain psychological tendencies: heightened sensitivity to fairness, difficulty with situations that feel competitive, or conversely, an exceptional drive to achieve and prove themselves.

Those who felt overlooked as children might become adults who struggle to ask for attention or support, while former “golden children” might battle perfectionism and fear of failure. Understanding these psychological patterns is the first step toward healing and growth. When we recognise that our adult reactions to competition, comparison, or feeling overlooked might stem from childhood sibling dynamics, we can begin to respond from our adult selves rather than our childhood wounds.

The Path Forward

Through a psychological lens, sibling rivalry emerges not as simple competition but as a complex interplay of attachment needs, identity formation, and social learning. It’s one of our earliest and most intense laboratories for learning about relationships, fairness, and our place in the world. This psychological understanding offers hope. The same relationships that once triggered our deepest insecurities can become sources of profound healing and growth. When we understand the psychological forces at play, we can transform rivalry into connection, competition into collaboration, and childhood wounds into adult wisdom.

The little girl sitting on the terrace in Jaipur, feeling invisible and displaced, couldn’t have known that her pain contained the seeds of understanding—not just for herself, but for the countless families she would later help navigate the complex psychology of sibling relationships.

References +

- Adler, A. (1927). Understanding Human Nature. Garden City, NY: Garden City Publishing.

- Bhugra, D. (2009). Terri Apter (2007). The sister knot: Why we fight, why we’re jealous and why we’ll love each other no matter what. International Review of Psychiatry, 21(5), 490. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701284570

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books. Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117-140.

- Kramer, L. (2014). Learning emotional understanding and emotion regulation through sibling interaction. Early Education and Development, 25(2), 160–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2014.838824

- Salmon, C. (2003). Birth order and relationships. Human Nature, 14(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-003-1017-x

- Schachter, F. F., Shore, E., Feldman-Rotman, S., Marquis, R. E., & Campbell, S. (1976). Sibling deidentification. Developmental Psychology, 12(5), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.12.5.418

Leave feedback about this