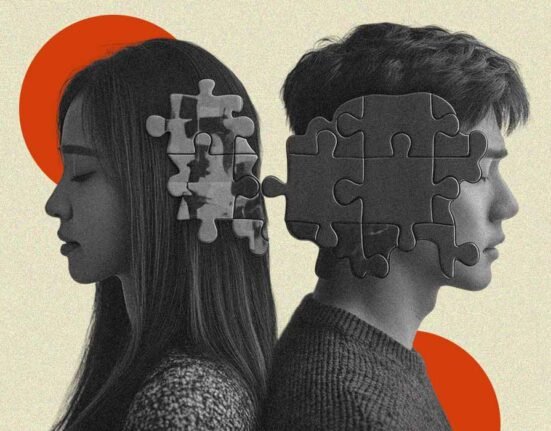

What does it mean to be “you”? Is it the body you inhabit, the voice in your head, your memories or something deeper, more elusive? The sense of self, while feeling natural and seamless, is actually the product of an intricate choreography within the brain. This invisible construction project involves multiple networks, each weaving together emotions, memories, sensations, and thoughts to shape a personal identity that feels stable yet evolves constantly.

The Brain’s Core Self-Constructing Machinery

At the core of this structure are two important brain areas that cooperate: the default mode network (DMN) and the cortical midline structures (CMS). Self-referential processing is mostly mediated by the CMS, which includes the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC). By combining information from several domains like language, emotion, and perception, these regions come to life when we reflect on ourselves, our characteristics, feelings, and the choices we make.

When the brain is “at rest,” meaning it is not concerned with the outside world, the DMN, and especially the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, is active. Yet that doesn’t imply it’s pointless. Rather, it’s busy constructing what scientists call the “self-in-context”, which is a model that pulls together information across time and sensory inputs to give personal meaning to events. This resting-state activity helps explain why your mind might wander to daydreams, past embarrassments, or imagined futures during idle moments. These reflections contribute to your narrative self, the story you tell about who you are.

The Multisensory Body: Bodily Self-Consciousness

Our sense of being located in our body of “me-ness” stems from what neuroscientists call bodily self-consciousness. This relies on the integration of multisensory signals: visual, proprioceptive, and vestibular, which are processed primarily in the fronto-parietal cortex and temporo-parietal junction. This region gives us our first-person perspective and sense of agency. A striking example is the rubber hand illusion, where synchronously stroking a rubber hand and a hidden real hand can trick the brain into adopting the fake one as its own. Such illusions demonstrate how flexible and fragile the sense of body ownership can be. Similarly, self-orientation in space requires the vestibular system, which helps with head position and balance. Without it, our bodily self would feel unanchored, as seen in certain vestibular disorders or out-of-body experiences.

The Layers of the Self: Awareness, Knowledge, and Emotion

Self-awareness provides an additional dimension, whereas physical awareness establishes the framework. This is the capacity for introspection, evaluation, and third-person self-perception.

According to neuroscientist Philippe Rochat, it develops gradually, starting with self-recognition in a mirror and ending with an awareness of one’s own characteristics and moral identity. Self-knowledge, which encompasses both the global self-concept (our lasting self) and the functioning self-concept (who we are at the moment), is the result of self-awareness. Inner speech becomes important in this situation. Not only does our inner monologue assist us in organising and practising dialogues that contribute to maintaining the coherence of our identity. Emotion and memory further shape this. The left amygdala and right orbitofrontal cortex regulate emotional interference in working memory, helping us remember emotionally salient events that define us. This emotional imprinting helps us recall who we were during major life events and how those moments continue to shape our current selves.

The Adaptability and Vulnerability of the Self: Drugs and Separation

What happens when the brain’s self-processing goes error? Dissociation, as seen in trauma or under substances like ketamine, can fracture the sense of self. Ketamine was found to reduce the brain’s ability to distinguish between touch created by oneself and touch produced by others. This blurring of boundaries reveals just how delicate the architecture of self can be and how dependent it is on neurochemical balance.

The Emergence of Self: From Womb to World

The construction of self doesn’t begin at adulthood or even at birth. It begins in the womb, where the foundations of awareness are supported by early sensory and cognitive functions. As children mature, they reach important developmental milestones, including identifying themselves in mirrors, using first-person pronouns, and comprehending their feelings. Autobiographical memory, which forms personal identity, is intricately linked to this development.

Theoretical Frameworks: Can Consciousness Be Modelled?

Several theories attempt to explain how the brain gives rise to the subjective sense of self. The temporospatial theory of consciousness posits that consciousness depends on the alignment between internal neural activity and external stimuli which is called “world-brain alignment.” This coordination ensures we can adapt and behave meaningfully in the world. Other frameworks, like Integrated Information Theory and Global Workspace Theory, propose that consciousness arises from how information is shared or integrated across the brain’s architecture. These help explain how different forms of self: bodily, emotional, autobiographical, can coexist within a unified conscious experience.

The Self as a Functional Illusion

As intuitive and real as the self feels, many scholars argue it’s a useful illusion. According to psychologist Bruce Hood (2001), the self is a construct that is an interface that helps us navigate social life. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio (2010) takes a similar view: the brain constantly maps the body in space and time, creating a minimal self that supports consciousness. Over time, these mappings grow more complex, giving rise to identity, self-reflection, and moral reasoning.

Why Understanding the Self Matters?

Understanding how the brain generates our sense of self is not only a philosophical pursuit. It is essential for diagnosing and treating conditions like schizophrenia, where self-limitations are often disrupted. It is essential to learn about dissociation, trauma, and even everyday experiences like meditation or altered states of consciousness. Future studies may be able to better customise treatments to mend a damaged sense of self as they reveal how individual-specific brain circuitry creates our distinct experiences.

Conclusion

Our sense of self is not a fixed entity but a continuous mental construction, crafted by the brain’s intricate dance between perception, memory, emotion, and bodily signals. As science unravels these complex networks, it becomes clear that who we are is not just felt but carefully assembled within us, moment by moment.

FAQs

1. Can the sense of self be lost or altered?

Yes, in conditions like depersonalization disorder or schizophrenia, individuals may feel disconnected from themselves. Brain injuries and psychedelic experiences can also alter self-perception temporarily.

2. Do animals have a sense of self?

Some animals, like great apes, dolphins, and elephants, show self-awareness in mirror tests. However, their sense of self may differ from the complex human self involving memory, language, and identity.

3. Is the sense of self fully developed in children?

No, the self develops gradually. Infants first form bodily awareness, while autobiographical memory and identity solidify during adolescence as brain regions like the prefrontal cortex mature.

4. Can technology or virtual reality affect our self-perception?

Yes, virtual reality can manipulate bodily self-consciousness and create illusions of being in another body, offering both therapeutic potential and risks for self-identity.

5. What happens to the sense of self in dementia?

As dementia progresses, especially Alzheimer’s disease, autobiographical memory fades. This leads to erosion of the narrative self, though some aspects of bodily or emotional self may persist.

References +

- Alicke, M. D., et al. (2020). Self and social judgment. Handbook of Self and Identity.

- Blanke, O., et al. (2015). Bodily self-consciousness: Neural mechanisms. Neuron. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.013

- Coppola, J., et al. (2024). Functional connectivity states and the self. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2024.00013

- Damasio, A. (2010). Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain.

- Hood, B. M. (2001). The Self Illusion.

- Kaldewaij, R., et al. (2024). Ketamine and self-perception. Biological Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2024.01.002

- Kanaev, D. (2023). Temporospatial theory of consciousness. Neuroscience and Consciousness. https://doi.org/10.1093/nc/niad008

- Levens, S. M., et al. (2011). Emotional interference and self-representation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2010.21508

- Leisman, G., et al. (2024). Fetal neurodevelopment and consciousness. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2024.00001

- Morin, A., & Everett, J. (1990). Inner speech and self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin.

- Olivé, G., et al. (2014). Superior colliculus and self-location. Neuroimage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.026

- Pfeiffer, C., et al. (2014). Vestibular contributions to bodily self. Current Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.020

- Sass, L. A., et al. (2003). Schizophrenia, self-disorder and consciousness. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology.

- Zhao, H., et al. (2023). Body ownership illusions. Brain-Inspired Intelligence. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bii.2023.101029

Leave feedback about this