What drives employees to give their best or hold back at work? The answer lies not just in rewards or job titles, but deep within the cognitive and behavioural processes that impact their actions. This article delves into the psychological underpinnings of employee motivation, exploring how cognition, biases, and behaviour patterns shape attitudes, influence motivation. It further explores challenges organisations face in sustaining motivation, alongside evidence-based strategies that enhance productivity. With a blend of theoretical insights and empirical findings, we uncover how understanding the mind can lead to meaningful change in the workplace.

Read More: The Psychology of Workplace Belonging: Driving Engagement & Productivity in Hybrid Workplaces

A Conceptual Dive into Cognitive and Behavioural Processes

Understanding employee behaviour in the workplace requires a dual lens. In contrast to cognitive processes, which aim to explain behaviour via mental processes, behavioural processes aim to explain behaviour through interactions with the environment (Markovits & Weinstein, 2018). Workplace’s cognitive and behavioural processes significantly impact how employees feel, think, and act in their work surroundings.

As defined by the American Psychological Association, cognitive processes have a role in the gathering, storing, interpreting, manipulating, transforming, and application of knowledge, which include tasks like attention, perception, learning, presupposing that cognitive processes are both serial and parallel, depending on the requirements of the task. Similarly, behavioural processes comprehend psychological phenomena to explain and emphasise observable features of behaviour. In the workplace, it refers to people’s interactions, perceptible behaviours, and responses to a range of situations and stimuli, which cover the actions that employees take while they cooperate, communicate, and work towards the organisation’s objectives.

Inside Motivation: The Role of Cognitive and Behavioural Dynamics

With this understanding, let’s explore key cognitive and behavioural processes that influence employee motivation and the challenges they present with research evidence.

How Perception Shapes Employee Motivation

Perception in the workspace is the way by which people interpret and make sense of sensory data from their surroundings, which affects how they perceive tasks, coworkers, and circumstances. According to Cha and Carrier (2016), perceptions of workplace support and working conditions have an impact on employee and organisational interactions.

As a result, highly successful organisations typically offer top-notch advantages for attracting and retaining engaged personnel. Support from the supervisor is moderately correlated with employee perception, suggesting a connection between the position and support of the supervisor and several factors that affect how supportive the workplace is seen to be. Similarly, an employee with a low opinion of the incentive policies and as well as a poor perception of their supervisor’s support and prospects for professional advancement, may result in their motivation to suffer (Ullah et al., 2017).

1. Challenges of Perception: Perceptual Errors, Negative Attributional Style, Horn and Halo Effect

Perception errors can occur at work as a result of inadequate knowledge and flawed self-evaluation (Mergan, 2018). Negative attributional style is negatively connected to job motivation, as it was discovered that individuals who have worked for a company for a considerable amount of time (more than 4 years) are particularly susceptible to a negative attributional style (Xenikou, 2005).

A negative halo effect, or horn effect, may happen when negative arousal coming from the presence of bullying is mistakenly attributed to bad supervisor traits. Such an association exists between reports of exposure to workplace bullying and subordinates’ judgements of supervisor personality (Mathisen et al., 2011), causing not only an evident attrition of employees, but also a toxic work environment.

Read More: Toxic Workplaces: Signs, Impact and Solution

How Attention Shapes Employee Motivation

Attention at the workplace can be regarded as the deliberate concentration of an employee’s mental energies on particular tasks, deciding what data is prioritised and processed. When top-down attention is present, it changes behaviour by prioritising task-related stimuli above information that is not relevant to the task at hand. Such behaviour is shaped by motivation, which reinforces similar behaviours that are believed to improve an employee’s environmental fitness (Engelmann et al., 2009).

1. Challenges of Attention: Attention Failures and Gaps, Poor Focus, Burnout

As literature suggests, delays in attention are common for people and occur frequently. Employees struggle to concentrate and focus, which increases their risk of making cognitive mistakes (Grossman, 2011). Such attention gaps and the inability to focus on a task have been linked to cognitive impairments (Klockner & Hicks, 2015).

Factors like task stresses and social stressors, such as workflow interruptions, may divert attention from the main activity and as a result, focus is diverted from the current task and is instead directed at the distraction, indicating that social stressors from supervisors and interruptions to supervisory-initiated workflow are likely to cause attention failure (Pereira et al., 2015). On similar lines, scientific evidence states that burnout is another key contributing factor to attention-related cognitive errors and absences when workers suffer job insecurity (Roll et al., 2019). Such attentional errors, in turn, decrease employees’ motivation to work.

Read More: How to Stay Focused in a World Full of Distractions

How Memory Shapes Employee Motivation

Memory in the context of the workplace can be the knowledge that is remembered and retained. Employees use memory to relate prior experiences to present duties and choices in the workplace. Memories symbolise an employee’s purpose or concern at work and thus become essential to one’s work. They do not serve as a redundant measure of motivation or general views of need satisfaction at work, as they can anticipate changes in motivation and psychological health over time. The findings of a study by Philippe et al. (2019) showed that self-determined motivation and signs of psychological well-being at work were connected to need fulfilment in self-defining work-related memories over time.

Read More: Improving Workplace Satisfaction, Motivation and Productivity Using Positive Psychology

1. Challenges of Memory: Cognitive Load Failures and Information Overload

Cognitive failures are thought to be linked to low attention, distraction, and mental errors that can lead to workplace accidents and incidents, which have a detrimental impact on alertness and memory performance (Abbasi et al., 2017). Prospective memory was found to strongly and adversely connect with occupational stress. The most likely explanation for this finding was that people tend to forget about some of the numerous engagements that needed to be attended to in the near future when their workload was heavy and they were working on many activities at once (Pande & Gupta, 2014). Results indicated that role ambiguity and role conflict were considerably exacerbated by information overload and system feature overload, which in turn caused a large rise in burnout expressed as emotional weariness and a reduction in personal success and turnover intention (Cho et al., 2019).

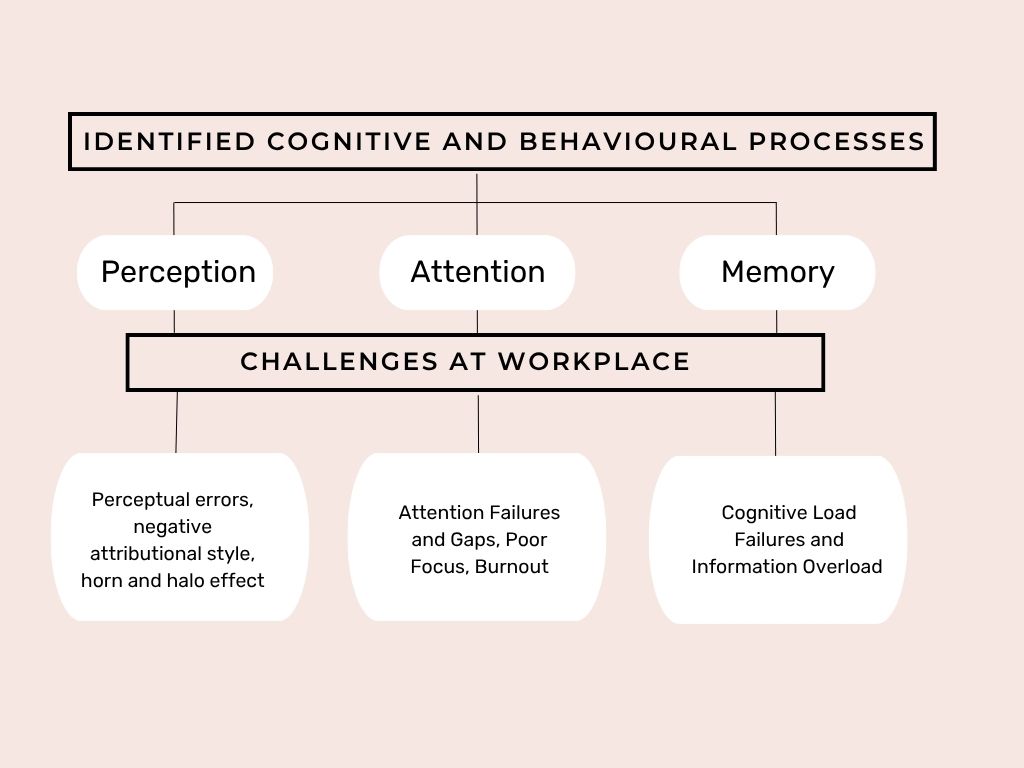

Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the key cognitive and behavioural processes identified, along with the challenges they pose that can hinder employee motivation.

Figure 1.

Organisational Strategies to Combat Cognitive Biases at Work

To boost employee motivation and productivity, organisations often rely on targeted strategies to address cognitive errors and behavioural challenges in the workplace. This section explores some of the most effective tactics used by companies.

Read More: Cognitive Biases That Secretly Control Your Decisions – And How to Outsmart Them

1. Incentives, Financial and Non-Financial Rewards

Most employees need motivation to perform their best. Some workers are driven by financial gain, while others are personally motivated by praise and awards (Ganta, 2014). The best chance of changing an industry’s performance and productivity is through the provision of relevant incentives (Barg et al., 2014). Such incentives can be extrinsic rewards that are not financial or intrinsic rewards, which are pay, bonuses, allowances, insurance, incentives, promotions, and job stability.

In contrast, the non-financial benefits include recognition, meeting new difficulties, an employer’s caring attitude, and gratitude. Research evidence suggests that monetary considerations, including financial incentives like wages, salary, bonuses, fringe benefits, health insurance, and life insurance, are important elements influencing how motivated and productive individuals are in their jobs (Yousaf et al., 2014).

2. Mindfulness Training and Therapies

According to empirical research, there is a strong inverse relationship between mindfulness and cognitive failure, meaning that mindfulness lowers cognitive failure ratings. The findings of a study appear to confirm the literature’s emphasis on the benefits of mindfulness training and therapies, as improved mindfulness abilities and reactions are linked to a reduction in cognitive errors (Klockner & Hicks, 2015). According to Mrazek et al. (2012), a brief exercise in mindful breathing was performed before a ‘Sustained Attention to Response Task’, and the results showed that this easy breathing technique decreased mind-wandering and enhanced sustained attention. Similarly, according to Good et al. (2016), as a result of mindfulness training, attentional efficiency improved employees’ mental productivity by training people to keep their thoughts focused and free of distractions.

Read More: The Power of Mindfulness in the Workplace

3. Employee Assistance Programs (EAP)

Employee Assistance Program’s objective is to locate employees’ concerns and assist them in finding solutions, either directly or through referral procedures. As a result, Employee Assistance Programs might be regarded as essential for organisational sustainability. When the ego-strengthening, personality development, and improvement of employees’ problem-solving skills were all taken into account by several industries in their employee support frameworks, research findings implicated that these industries placed a strong emphasis on providing their employees with a high-quality work environment, by setting up workplace health and safety measures as well as social, cultural, and wellness initiatives for their employees (Ghosh, K. (2020).

Overall, Employee Assistance Programs can result in positive clinical change, increases in presenteeism and functioning, decreases in illness, disability, or workers’ compensation claims, and improvements in employee absenteeism, productivity, and turnover (Attridge et al., 2009; Joseph et al., 2018), altogether.

Concluding Analysis: Cognitive and Behavioural Impact on Employee Performance

Taking into account the evidence discussed, it is clear that employee performance and productivity significantly improve when cognitive challenges are minimised through dynamic organisational strategies. Cognitive processes such as perception, attention, and memory play a crucial role in shaping employee motivation. Challenges like perceptual errors, negative attributional styles, attention lapses, and cognitive overload can hinder both employee and leadership effectiveness.

However, through targeted strategies such as incentives, mindfulness interventions, feedback mechanisms, and employee assistance programs, these challenges can be mitigated. This article concludes that employee motivation, productivity, and performance are deeply influenced by the interplay of cognitive and behavioural processes, and that organisations can enhance outcomes by implementing research-backed, well-designed strategies. These efforts ultimately contribute to building a motivated, empowered, and high-performing workforce.

Figure 2 illustrates how the impact of cognitive-behavioural processes and the challenges they present shifts positively once targeted strategies are implemented. These interventions help boost employee motivation, which in turn leads to improved performance and overall productivity.

Figure 2.

References +

Abbasi, M., Zakerian, A., Mehri, A., Poursadeghiyan, M., Dinarvand, N., Akbarzadeh, A., & Ebrahimi, M. H. (2017). Investigation into the effects of work-related quality of life and some related factors on cognitive failures among nurses. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 23(3), 386-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2016.1216991

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.). https://dictionary.apa.org/behavioral-psychology

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.). https://dictionary.apa.org/cognitive-process

Attridge, M., Amaral, T., Bjornson, T., Goplerud, E., Herlihy, P., McPherson, T., Paul, R., Routledge, S., Sharar, D., Stephenson, D., & Teems, L. (2009). EAP effectiveness and ROI. EASNA Research Notes, Vol. 1, No. 3. Available online from http://www.easna.org.

Barg, J. E., Ruparathna, R., Mendis, D., & Hewage, K. N. (2014). Motivating workers in construction. Journal of Construction Engineering, 3(2), 21-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/703084

Cha, M. Y., & Carrier, C. (2016). Contingent faculty perceptions of organisational support, workplace attitudes, and teaching evaluations at a public research university. Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education, 1, 121-151. Retrieved from http://www.jspte.org/Volume1/JSPTEv1p121-151Cha2261.pdf

Cho, J., Lee, H., & Kim, H. (2019). Effects of Communication-Oriented Overload in Mobile Instant Messaging on Role Stressors, Burnout, and Turnover Intention in the Workplace. International Journal of Communication, 13, 21. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/9290

Engelmann, J. B., Damaraju, E., Padmala, S., & Pessoa, L. (2009). Combined effects of attention and motivation on visual task performance: transient and sustained motivational effects. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 3, 342. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.004.2009

Ganta, V. C. (2014). Motivation in the workplace to improve employee performance. International Journal of Engineering Technology, Management and Applied Sciences, 2(6), 221-230.

Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., … & Lazar, S. W. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work: An integrative review. Journal of Management, 42(1), 114-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617003

Ghosh, K. (2020). Employees assistance programme: social work at the workplace: An evidence based review. International Journal of Social Sciences, 9(4), 301-306. DOI:10.30954/2249-6637.04.2020.12

Grossman, P. (2011). Defining mindfulness by how poorly I think I pay attention during everyday awareness and other intractable problems for psychology’s (re) invention of mindfulness: comment on Brown et al.(2011). DOI: 10.1037/a0022713

Joseph, B., Walker, A., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of employee assistance programmes: a systematic review. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 27(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1374245

Klockner, K., & Hicks, R. E. (2015). Cognitive failures at work, mindfulness, and the Big Five. GSTF Journal of Psychology (JPsych), 2, 1-7. DOI 10.7603/s40790-015-0001-3

Markovits, R. A., & Weinstein, Y. (2018). Can cognitive processes help explain the success of instructional techniques recommended by behaviour analysts? Npj Science of Learning, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-017-0018-1

Mathisen, G. E., Einarsen, S., & Mykletun, R. (2011). The relationship between supervisor personality, supervisors’ perceived stress and workplace bullying. Journal of Business Ethics, 99, 637-651. DOI 10.1007/s10551-010-0674-z

Mergan, N. M. (2018). Workplace Interactions and the Influence of Perceptions. Stamford International University.

Mrazek, M. D., Franklin, M. S., Phillips, D. T., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychological Science, 24(5), 776-781. DOI: 10.1177/0956797612459659

Pande, N., & Gupta, S. (2014). Occupational stress, cognition, and affect among university employees: A correlational study. International Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 2(1), 57-64. DOI : 10.5958/j.2320-6233.2.1.008

Pereira, D., Müller, P., & Elfering, A. (2015). Workflow interruptions, social stressors from supervisor (s) and attention failure in surgery personnel. Industrial health, 53(5), 427-433.

Philippe, F. L., Lopes, M., Houlfort, N., & Fernet, C. (2019). Work-related episodic memories can increase or decrease motivation and psychological health at work. Work & Stress, 33(4), 366-384.https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1577311

Roll, L. C., Siu, O. L., Li, S. Y., & De Witte, H. (2019). Human error: The impact of job insecurity on attention-related cognitive errors and error detection. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(13), 2427.

Ullah, Z., Khan, M. Z., & Siddique, M. (2017). Analysis of employees’ perception of workplace support and level of motivation in a public sector healthcare organisation. Business & Economic Review, 9(3), 240-257. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.22547/BER/9.3.10

Xenikou, A. (2005). The interactive effect of positive and negative occupational attributional styles on job motivation. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 14, 43 – 58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320444000218.

Yousaf, S., Latif, M., Aslam, S., & Saddiqui, A. (2014). Impact of financial and non-financial rewards on employee motivation. Middle-East journal of scientific research, 21(10), 1776-1786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ admsci12040161