The search for meaning in life is a basic human aspiration, intersecting the desire to find purpose and significance in our situation. This pursuit concerns how people experience their situations and relations and, ultimately, define themselves and their way ahead. The literature highlights that meaning-making is associated with increased resilience, satisfaction, and good mental health (Park, 2010)[1].

Theories surrounding meaning-making vary but share principles highlighting intrinsic motivation and self-awareness. Self-determination theory posits that fulfilling needs for autonomy, competence, and connection fosters a deeper sense of meaning (Paul Wong, 2012, pages 6-10)[4]. This aligns with humanistic-existential theories promoting authentic engagement with personal values.

Making meaning involves integrating both positive and negative experiences to create a cohesive narrative (Paul Wong, 2012, pages 6-10)[4]. This dual approach can enhance coping strategies during adversity while amplifying happiness (Yoshitaka Iwasaki, 2008, pages 11-15)[5]. Integrative thinking recognises the nuances of human life, where subjective meanings come into contact with objective truths.

Engaging in activities that foster connections significantly influences the development of meaningful lives (Yoshitaka Iwasaki, 2008, pages 11-15)[5]. Understanding meaning-making points out essential aspects of individual behaviours and societal norms, underscoring its vital role in psychological health.

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding Meaning

The investigation into the nature of meaning-making in life can be significantly enhanced through various theoretical lenses, particularly those rooted in humanistic psychology and narrative psychology. Leading contributors such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers have spearheaded humanistic psychology with the notion that self-actualisation, creativity, and individuality form pillars for personal growth and seeking meaning (as reflected in (Kendra Cherry, 2024)[6]. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs demonstrates that self-actualisation—achieving one’s highest capabilities—is a basic element for seeking a meaningful existence.

In parallel, narrative psychology makes our knowledge more complete by focusing on how people create individual narratives that form their identities. The narratives people create about their lives enable them to interpret experiences and establish a cohesive sense of self (as referenced in (Singer, 2004)[2]. This story-building process is dynamic; it evolves over time as individuals face new challenges and reframe past experiences (according to Robyn Fivush, 2017)[3].

Additionally, positive psychology sheds light on the relationship between happiness, individual strengths, and overall well-being with meaning in life. It suggests that nurturing positive emotions and fostering personal development are essential for achieving true fulfilment (see (Psychology (PSYCH) | Penn State, 2025)[9] for more information). Steger’s cognitive perspective on meaning encapsulates this idea by proposing that meaning is composed of connections and interpretations that empower individuals to steer their efforts toward desired outcomes (Paul Wong, 2012, pages 6-10)[4]. Therefore, amalgamating these theories offers a rich and nuanced understanding of how people navigate their quest for purpose amidst the intricacies of life.

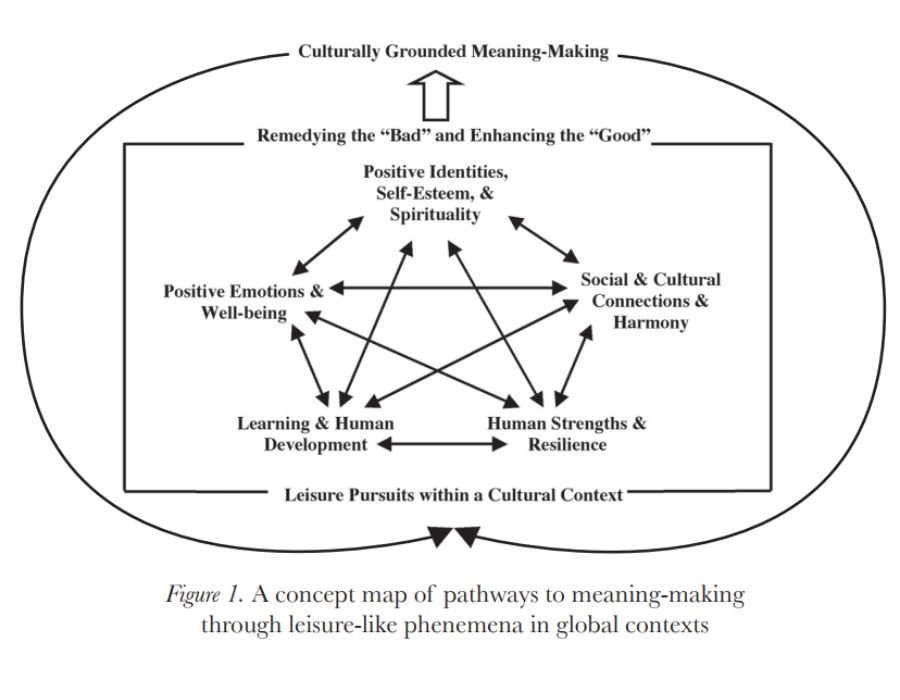

Figure 1: A concept map of pathways to meaning-making (source: reference (Yoshitaka Iwasaki, 2008)[5]

Lifespan Development and Evolution of Meaning-Making

Lifespan development significantly influences meaning-making processes. In childhood, individuals begin to form their understandings of purpose and identity, shaped by familial interactions and culture. According to Fivush et al. (Robyn Fivush, 2017)[3], narrative meaning making progresses through engagement with surroundings, enhancing children’s storytelling abilities. Adolescence marks a crucial transformation where identity formation takes precedence. De Moor (Moor, 2023)[11] notes that adolescents often intertwine personal narratives with broader life stories, enriching self-event connections and coherence.

As adults, the pursuit of goals becomes vital for creating meaningful lives. Singer (Singer, 2004)[2] emphasizes that narrative identity evolves as individuals integrate diverse experiences—trials and triumphs—into cohesive life stories that promote personal unity. This integration fosters psychological resilience and well-being.

In later years, reflection emerges as a key theme; older individuals often reevaluate their purposes and intentions for legacy, seeking to contribute to future generations. This reflective journey compels older adults to explore past experiences, constructing narratives that embody core values and insights gained throughout life (Singer, 2025)[8]. By modifying their narratives in response to experiences, individuals can make out meaning that helps ongoing psychological growth across their lifetimes.

Sociocultural Influences on Meaning Construction

Sociocultural forces are essential for meaning construction in people’s lives. Cross-cultural research indicates that cultures have different value systems, which shape perceptions of what is important. Western cultures tend to emphasise individualism and personal achievement as prime sources of purpose, whereas collectivist cultures emphasise community and family bonds as vital sources of meaning. These varied values influence the stories people construct about their past and future.

Cultural stories are essential in the formation of individual purpose, providing frameworks whereby individuals make sense of life experience and create identity. Passed-down stories teach lessons in resilience, ethics, and belonging, and create a sense of identity with one’s origins and place in the larger scheme of things. Social relationships also offer an effective avenue for discovering meaning. Close family and friendship ties give emotional support that boosts self-esteem and sense of belonging. Empirical research shows that adults who come from varied backgrounds perceive these relationships as major sources of inspiration (Murthy, 2023, pages 31-35)[14].

Additionally, community involvement expands the importance of relationships, fostering social bonding and mutual experience that supports psychological resilience. Group participation establishes a collective sense of direction while offering emotional support, highlighting the relational aspects essential for overall well-being.

Implications for Psychological Resilience, Well-Being, and Clinical Recovery

The relationship between meaning-making and mental health is intricate. A robust sense of meaning in life (MiL) is found to improve psychological resilience, particularly in the context of trauma. Those who are confronted with serious adversity, including illness, are better able to cope if they possess a firm MiL, frequently experiencing post-traumatic growth (PTG) through the creation of purpose in the face of adversity. Without meaning, anxiety and depression may improve (Almeida et al., 2022)[10].

In treatment, assisting clients to define their values, beliefs, and intentions is important for the inclusion of meaning in their lives. Therapists employ methods such as positive reframing and goal setting to help clients better establish purpose (Posluns & Gall, 2019)[13]. Meaning-based therapies emphasise narrative therapy, with the use of storytelling enabling clients to reconstruct their narratives of trauma, aligning personal meanings with more general existential realities.

Trauma-informed methods appreciate that people struggle with questions of existence following the experience of trauma. Narrative therapy allows clients to resolve such questions and engage in hope through narrative reinterpretation. Through constructing meaningful stories that include distressing recollections, people find meaning and make progress towards healing (Paul Wong, 2012, pages 11-15)[4]. This holistic approach takes care of emotional upheaval while facilitating personal growth and resilience.

Conclusion: Navigating Ambiguity and Purpose

To navigate the meaning-making maze is paramount for seekers of meaning, especially during the inherent uncertainties of the human condition. A convergence of key findings identifies meaning-making as a dynamic, delicate process influenced by a range of factors such as personal development, sociocultural settings, and existential considerations. Theoretical frameworks developed within humanistic psychology emphasise the role of self-actualisation and personal responsibility as central aspects in the quest for meaningfulness (as referenced in Humanistic psychology, 2025[12] and Saul McLeod & Olivia Guy-Evans, 2025)[15].

Additionally, comprehending how individuals derive meaning from challenging experiences can bolster psychological resilience and aid recovery efforts (according to (Park, 2005)[7]). An expanding body of research highlights the role leisure activities play in this journey, as they encourage engagement and exploration of values across varied cultural landscapes (Yoshitaka Iwasaki, 2008, pages 11-15)[5].

Looking ahead, future research endeavours should strive to broaden the global understanding of meaning-making, taking into account its significance within diverse cultural contexts. Delving into how emerging technologies influence our conception of purpose may also yield enlightening perspectives. By cultivating interdisciplinary frameworks that meld psychological theories with sociocultural dynamics, researchers can further enrich the ongoing conversation about enhancing human well-being through meaningful existence.

FAQs

1. What does “meaning in life” actually refer to in psychology?

In psychology, meaning in life refers to the subjective sense that one’s existence is coherent, purposeful, and significant. It involves how individuals interpret experiences, connect to others, and align their actions with values, contributing to identity, well-being, and psychological stability.

2. How do different psychological theories explain the construction of meaning in life?

Theories like humanistic psychology focus on self-actualisation, while narrative psychology emphasises life stories. Self-determination theory highlights autonomy and connection, and positive psychology links strengths and goals to fulfilment.

3. How does meaning-making evolve throughout an individual’s life?

Meaning evolves across life stages—from early family influence in childhood to identity formation in adolescence, purposeful striving in adulthood, and reflective integration in old age.

4. What role do culture and society play in shaping meaning-making?

Cultural stories, social bonds, and shared beliefs shape identity, resilience, and the pursuit of meaningful living.

5. How is meaning in life related to mental health, resilience, and trauma recovery?

A strong sense of meaning enhances psychological resilience, helps manage adversity, and supports trauma recovery. It fosters post-traumatic growth and reduces distress.

6. Can modern technologies and digital life affect how we construct meaning today?

Digital platforms allow people to express identity and find community, aiding meaning-making. However, online comparison and superficial engagement can hinder authenticity.

References +

- Park. Crystal L.. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events.. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2010-03383-011.html

- Jefferson A. Singer. (2004). Narrative Identity and Meaning Making Across the Adult Lifespan: An Introduction. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8602864_Narrative_Identity_and_Meaning_Mak ing_Across_the_Adult_Lifespan_An_Introduction

- Robyn Fivush.Jordan A. Booker.Matthew E. Graci. (2017). Ongoing Narrative Meaning Making Within Events and Across the Life Span – Robyn Fivush, Jordan A. Booker, Matthew E. Graci, 2017. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0276236617733824

- Paul Wong (2012). http://www.drpaulwong.com/documents/HQM2-intro.pdf

- Yoshitaka Iwasaki. Ph.D.. (2008). Pathways to Meaning-Making Through Leisure-Like Pursuits in Global Contexts. https://www.nrpa.org/globalassets/journals/jlr/2008/volume 40/jlr-volume-40-number-2-pp-231-249.pdf

- Kendra Cherry. MSEd. (2024). How Humanistic Psychology Can Help You Live a Better Life. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-humanistic-psychology-2795242

- Crystal L. Park. (2005). Religion as a Meaning-Making Framework in Coping with Life Stress. https://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00428.x

- Singer. Jefferson A.. (2025). Narrative Identity and Meaning Making Across the Adult Lifespan: An Introduction.. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-14459-001

- Psychology (PSYCH) | Penn State. (2025). https://bulletins.psu.edu/university-course descriptions/undergraduate/psych/

- Almeida. Margarida, Basto-Pereira. Miguel, Leal. Isabel, Maciel. Laura, Ramos. Catarina. (2022). Frontiers | Meaning in life, meaning-making and posttraumatic growth in cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.995981/full

- Elisabeth L. de Moor. (2023). Meaning making about and across self-relevant experiences: Links with identity commitment and exploration processes and satisfaction with life in adolescence. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009265662300096X

- Humanistic psychology. (2025). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanistic_psychology

- Kirsten Posluns, Terry Lynn Gall. (2019). Dear Mental Health Practitioners, Take Care of Yourselves: a Literature Review on Self-Care. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7223989/

- Vivek H. Murthy. (2023). Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf

- Saul McLeod. PhD, Olivia Guy-Evans. MSc. (2025). Humanistic Approach In Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/humanistic.html